In the superstorm's wake

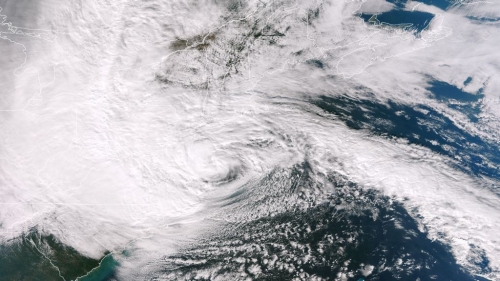

Hurricane Sandy approaches the Jersey shore. (Credit NASA/NOAA)

As hospitals evacuated and dark streets flooded, Villanova nurses had to navigate a drastically different world. Now some are taking part in the rebuilding.

First came the darkness.

As Hurricane Sandy descended upon New York City on October 29, 2012, Beth Israel Medical Center’s lights suddenly went out. When flood lamps illuminated the century-old hospital in Manhattan, Emergency Department nurse Sarah Skog ’07 B.S.N., R.N. braced for the worst. Manhattan’s lower East Side, almost always abuzz with flashing lights and the shouts of New Yorkers and tourists navigating streets, was almost entirely black. Like many of her colleagues, Skog assumed there would be “a rush of patients, horrific traumas and flooding in our own hospital.”

Instead, it was quiet. The surge didn’t come. People were stuck in their homes as water rushed down dark streets now littered with destroyed cars and downed trees.

After an eerie silence, the patients began to arrive—cold and wet, speaking of an outside world that seemed light years away from what New York had been just hours before.

“The EMS would come in drenched, saying they had swum to their patient, or out of breath after climbing multiple flights of stairs,” said Skog, who is originally from West Chester, Pa. “One elderly gentleman came in cold and wet. He owned a video store on the West Side. He said after the lights went out, he watched the water level climb up the doorway. He was in the cold, dark store for several hours before the glass broke and the water rushed in. He managed to get out of the store and walk a couple of blocks before finding an ambulance.”

The stories kept coming in. First responders told hospital staff that Bellevue Hospital Center—the country’s oldest public hospital—was flooded and evacuating patients. New York University Langone Medical Center generators had failed, and its staff was evacuating. Patients were being transferred to places like Beth Israel, and ambulances that would have once transported people to Bellevue or NYU were now arriving in force.

Like nurses throughout much of the Northeast, Skog barely stopped to rest during this superstorm—the largest Atlantic hurricane on record. It affected 24 states, from the Eastern Seaboard to the Midwest, and had winds spanning 1,100 miles. At least 253 people in seven countries died in connection with the storm, including at least 97 in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut.

Scog arrived at work around noon that Monday. It would be 16 hours before she could pause long enough to grab a hot meal at a deli and a nap at her nearby apartment, where there was no heat or electricity.

Her story from Superstorm Sandy is like those of many Villanova nurses—and countless medical personnel in general—throughout New York City, Long Island, New Jersey, Connecticut and beyond. They speak of long nights and navigating a world drastically different from what they were used to. They talk of ERs spilling over with everyone from a cab driver who was trapped in his car after it filled with water to a woman in her 20s who sustained a head injury after being blown over in the wind following a “hurricane party.”

Like Skog, Kathryn Lenhardt ’08 B.S.N., R.N. practices at a hospital that remained open: New York-Presbyterian-Columbia Medical Center. She stayed on duty more than 12 hours a day for five days during, and in the immediate aftermath of, the hurricane. “One of the nurses I worked with showed her badge to a police officer who escorted her over the closed bridges and to the hospital so she could be there in time to work,” Lenhardt recalled. “I do have friends that worked at NYU and Bellevue, and they have stories of evacuation and the difficult challenges they faced.”

Sarah Buckley ’05 B.S.N., R.N., M.S.N., ACNP-BC worked for nine days straight at New York-Presbyterian-Weill Cornell’s ER. It was the only trauma center open in Manhattan during the hurricane.

“We were inundated with patients following the storm,” Buckley said. “During one hour on Wednesday, we had 32 patients arrive by ambulance. We saw a lot of power outage-related problems, such as many elderly people running out of oxygen, as their tanks ran on electricity. Some patients reported waiting four-plus hours for EMS to arrive after they called 911.”

The hospital had to expand its ER into the hallways and set up a patient care area in the lobby. With hospitals remaining closed in New York as of late December, the 52-bed ER coped with a population of 162.

“Our hospital has been quite innovating in trying to improve throughput in the ER,” Buckley said. “For example, the finance department lost power in their building, so they came to the ER and helped transport our patients, which helped reduce the length of stay.”

Through it all, Buckley said she felt “very fortunate personally. Working extra hours in the ER was the least I could do. People lost so much. I have family in Breezy Point that lost everything to fire. I think it is important to remember all those that are still affected by the destruction.”

Deborah “Debbie” Donahue Hayden ’90 B.S.N., R.N., who is the Red Cross volunteer Disaster Health Services (DHS) lead on Long Island, coordinated with area hospitals to make sure discharged patients got home safely. Yet this time, noted Hayden, “So many people had no homes to go to.”

A seasoned Red Cross volunteer, after Hurricane Irene hit last year Hayden managed the largest Red Cross shelter on Long Island, at Nassau Community College. She worked hard last September and October to involve local nursing students in the organization—an effort that made a huge difference when Sandy landed. More than 40 nursing students volunteered in Red Cross shelters. Between Sandy and the nor’easter that followed, the Red Cross managed more than 100 health service professionals to provide nursing care in 28 shelters.

“Picture a college gymnasium filled end-to-end with cots, blankets and evacuees,” said Craig Cooper, a spokesman for the Red Cross. “These folks arrive at our shelter and, while most are in good health, many present with issues that must be properly identified, documented or monitored. It is not uncommon for someone on diabetes, heart or asthma medication to miss or forget important doses. Debbie [Hayden] and her DHS team are right there to determine if a resulting episode can be managed in-house or should be immediately referred to a medical facility.”

Months after the hurricane hit, many people and communities are still hurting—and College of Nursing graduates are trying to help them.

Lauren Harrison ’96 B.S.N., R.N., a clinical research nurse in pediatric hematology/oncology at New York Medical College in Valhalla, N.Y., helped organize a supply drive at Manchester (Mass.) Memorial Elementary School, where her children attend. After collecting a truck full of supplies at her house, Harrison joined forces with Courtenay Gayeski Higgins '95 A&S to drop off them off in Manasquan, one of the devastated Jersey Shore communities.

“The streets were still filled with sand, four weeks later,” Harrison said. “The boardwalk in Point Pleasant was washed away… There were houses totally washed away….It was very humbling to be there and feel so helpless. We did what we could.” Harrison, who is also an adjunct professor at Endicott College in Beverly, Mass., plans to return with her children in the spring to help rebuild this Jersey Shore community.

Despite the tremendous difficulties, the immense amount of work done by nurses during, and after, the hurricane “shows that nurses are truly heroic,” Lenhardt said.

“During this difficult week, all the hospitals had been in disaster mode, with nurses on the front line caring for the injured and helping the city rebuild,” Lenhardt added. “We had numerous patients come in due to loss of power and their inability to care for themselves at home. Dialysis centers were closed and ventilator patients were coming in concerned. We are in an incredible profession and are often surrounded by such remarkable people.”