Aaron Bauer’s Legacy is Forged from Renowned Herpetology Research and Grown by Generations of Students

Dr. Bauer, a Biology professor in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, remains a steadfast pillar for current and aspiring herpetologists

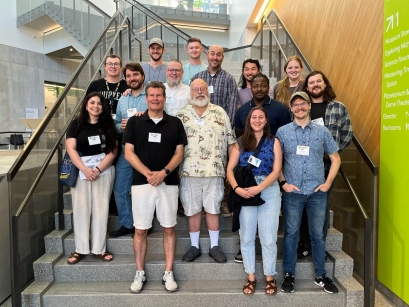

Generations of Dr. Bauer's students, many of them leading herpetologists themselves, pose with the renowned professor during the 2024 World Congress of Herpetology in Borneo.

Aaron Bauer, PhD, the Gerald M. Lemole Endowed Chair in Integrative Biology, stood smiling at the center of the group, dressed in a Hawaiian shirt and khaki shorts—the outfit that has become quintessential to the Villanova professor. Flanking him on both sides were 13 other herpetologists, ranging in age, origin, discipline and career stage.

A bystander snapped their photo, and they relaxed back into conversation. Dr. Bauer remained at the center.

The photo was taken at the 2024 World Congress of Herpetology in Borneo, but it might as well have been taken on Villanova’s campus. Each one of those 13 individuals—some as postdocs or undergrads, but mostly master’s students—studied in Dr. Bauer’s lab. At that meeting, he estimated Bauer Lab students and alumni (18 in total) constituted more overall attendees than any other institution, and even entire countries.

As the world’s foremost expert in geckos, and a dabbler in just about everything else, Dr. Bauer’s academic achievements are widely known and celebrated in the scientific community.

“He’s a present-day Charles Darwin,” said Elizabeth Patton ’25 MS, before correcting herself. “Actually, he’s probably more productive than Darwin.”

Dr. Bauer’s first species description—the formal scientific documentation of a new species—happened to be the largest gecko to ever exist, and the specimen he studied was the only one ever found. He has since described 310 new species of reptiles, more than any other living scientist and fifth-most all-time. An impressive 940 publications, including 54 published in a single year, bear his name.

“I’m not sure if that figure includes the two I described last week, though,” he interjected with a slight grin, although he was not joking.

There is even a species of gecko—Hemidactylus aaronbaueri, or Aaron Bauer’s house gecko—named in homage to his achievements.

But Dr. Bauer’s influence on the history, present and future of his field extends far beyond his Google Scholar page. It extends internationally and in in many ways began at Villanova University.

“It’s the ‘Aaron Bauer Pipeline,’” Patton said. “And it’s a very real thing.”

At Villanova, Dr. Bauer has helped shape the career paths for dozens of herpetologists. His guidance and collaboration with those former students continue long after they leave his lab.

By numbers alone, the “Aaron Bauer Pipeline” speaks for itself. Since 2000, a little more than a decade after he began teaching at Villanova, 50 master’s students have come through his research lab, and Dr. Bauer estimates 40 of them have gone on to obtain PhDs and remain in herpetology. Of those who didn’t, several work in other branches of zoology.

“We are populating the world with systematic herpetologists,” Dr. Bauer said with a laugh.

In its simplest form, the pipeline is this: his master’s students leave Villanova and most obtain their PhDs, largely remaining in herpetology—a crowded field—and academia. Many of them teach undergraduates, who they then recommend join Dr. Bauer’s lab for their master’s work. Some of those master’s graduates pursue their PhD under the guidance of previous pupils of Dr. Bauer’s. Currently, two of his former students are advising PhD candidates who also came from his program.

“It’s really cool to see a generation of Villanova master’s students going on to their careers and now mentoring the next generation,” Dr. Bauer said. “They know what our students are going to be like, because they have been through the program themselves.”

All the while, the entire cohort of Wildcat herpetologists support one another in research endeavors with collaborations often facilitated and nurtured by Dr. Bauer himself. His mentorship begins on arrival.

“I came to his lab with the interest, but didn’t know the community or how to begin,” Patton said. Dr. Bauer listened to her ideas, helped her cultivate relationships in the field and guided her toward a thesis project that aligned with her interests.

“Dr. Bauer is one of those people who can list five colleagues off the top of his head that would be able to help you,” Patton said. “Then he’ll put you in contact with them for possible collaboration and help you secure funding. He holds on to relationships for decades. It’s having a person on the inside, and not just anywhere on the inside, but the pillar.”

“They have a network to tap into,” Dr. Bauer said. “Sometimes, we have four or five people on a paper who didn't overlap with each other at all in my lab, but they have been in touch with one another because they came out of Villanova and have similar research interests. It’s a really rewarding thing to know there's a community carrying on with this work.”

That community, and no doubt the professor and researcher at the center of it, has attracted students to Villanova from across the planet: China, the United Kingdom, Angola, Türkiye and South Africa, to name a few.

“I came here from South Africa to study with him because he has that big of an influence in this field,” said Gary Nicolau ’25 MS.

“We attract students from all over the world,” Dr. Bauer said. “But then we send them back out all over the world to continue their contributions to the field.”

Pictured here with current and former students, Dr. Bauer (center) and Dr. Jackman (front, left) are complementary forces in the Biology department, helping prepare future leaders of the field in unique ways.

You might have to pry out of the humble professor the details of his career achievements, but ask him about the successes of his students, and he will talk for hours. Effusing praise for their drive and skill and speaking proudly of their post-Villanova adventures come as easy to him as discovering a new gecko.

He will also be the first to tell you that a professor just down the hall in the Mendel Science Center is a major reason his own master’s students have left Villanova with the toolkit they have.

“Todd Jackman is absolutely integral to everything we do,” Dr. Bauer said. “When he came here, the program really started to take off.”

Todd Jackman, PhD, professor of Biology and fellow herpetologist, joined Dr. Bauer at Villanova in the late 1990s. It was almost as if they were predestined to work together. Both professors earned their PhDs from University of California, Berkeley but never met—they missed one another by a year. Dr. Bauer’s future wife, who he met at UC Berkeley, was the lab technician who trained Dr. Jackman.

When the two researchers finally joined forces on the East Coast, it elevated the appeal of Villanova’s herpetology program for both prospective students and professors.

“Todd’s arrival at Villanova was a catalyst,” Dr. Bauer said. “After that, we could do everything in-house.”

Though their labs and research interests differ, the two are perfectly complementary. Dr. Bauer mainly concentrates on morphology and taxonomy and has carved a niche advising master’s students. Dr. Jackman’s forte is molecular systematics, and he often has undergraduate researchers working on projects. Each professor has his own separate research lab, but they do what Dr. Bauer calls a “huge amount of collaborative work.”

“My students either work in morphology, molecular systematics or both,” Dr. Bauer said. “Even though I am their advisor, if they had components of their research that fell into the molecular side, they would receive a lot of guidance from Todd.”

“If you were to go study morphology elsewhere, you might never be exposed to anything at the molecular level, like genes or bioinformatics,” Dr. Jackman said. “Or, you could end up in a molecular lab where you never actually get to see or hold an animal in your hand. Together, we provide both of those things, plus the field work. There’s a real synergy.”

Arianna Kuhn, PhD, ’11 CLAS, ’16 MS, benefited from that synergy from the time she stepped foot on campus as a first-year student until she left with her master’s degree. Dr. Jackman advised her summer and independent undergraduate research, but Dr. Bauer was her senior thesis advisor, and she was formally a master’s student in his lab. Dr. Kuhn, who says the two professors were foundational to her career success, was recently named Herpetology Curator at the Illinois Natural History survey within the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s Prairie Research Institute.

For master’s students like Ed Stanley, PhD, ’09 MS, associate scientist with the University of Florida’s Florida Museum of Natural History, the work in each lab was concurrent and condensed into his time in the graduate program. The molecular work on his thesis—investigating the DNA-based evolutionary relationships of a group of African lizards—was done under the guidance of his advisor, Dr. Jackman. At the same time, Dr. Bauer was finding Dr. Stanley opportunities for intensive field work and helping him engage with the historical and biological meaning of his work.

Dr. Stanley—who came to Villanova from Scotland unsure of his career goals—is now considered the world’s foremost expert in the use of micro-computer tomography (CT) scanning to study the evolution of snakes, lizards and amphibians. His current PhD candidate recently completed master’s-level work with Dr. Bauer, and the professor continues to collaborate with both Drs. Bauer and Jackman on numerous projects.

“All of us are connected, and that tether keeps growing longer,” Dr. Stanley said. “You might be out the door [at Villanova], but that door of opportunities never closes.”

Dr. Bauer searches for a book on one of the bookcases in his home library. His collection of 20,000 herpetology texts—and his knowledge of each of them—are inavulable and otherwise inacessible resources for students.

In the 2012 movie “The Amazing Spiderman,” the superhero’s nemesis—an evil reptile researcher aptly named “The Lizard”—is depicted in a scene in front of his large scientific library. But during production, the filmmakers received feedback that their library didn’t look very scientific. One of them contacted a professor he knew at Villanova University—a professor with the largest collection of herpetology texts in the world. That collection ultimately served as the model for the film.

Dr. Bauer’s personal library, which he calls his hobby, fills more than just a few rooms in his home and features upward of 20,000 texts in various languages, spanning several centuries and countless subjects. This unrivaled collection, and Dr. Bauer’s vast comprehension and retention of the material, gives his students invaluable—and otherwise inaccessible—access to resources. He uses some of them for curated readings in his coursework and discussions and often draws from them to answer specific questions from students. Dr. Stanley refers to his knowledge as “truly encyclopedic” and Patton calls it the “widest and deepest” of anyone she has ever met.

“And because of that knowledge, no matter what your interests are, he's able to point you in the right direction,” Nicolau said.

“His understanding of the natural world comes from a sense of wonder that has been kind of lost in the modern era,” said Phil Skipwith, PhD, ’11 MS, assistant professor of Biology at The University of Kentucky. “And you now see that in so many of the students that have come through his lab.”

Indeed, a common thread among Dr. Bauer’s students is the contagious sense of curiosity they learn from him. They revel in sharing anecdotes showcasing how his bewildering mastery of literature helped their own studies.

“He'll pull out some obscure, 18th-century text that only exists physically in his living room to reference something,” Nicolau said. “Once we were talking about an ancient species, and he made a point referencing the climate in Eritrea 15,000 years ago.”

“He can read Afrikaans and also speaks English, German, French and Latin, as good as anyone speaks Latin these days,” Patton said. “You might come across a handwritten German journal that you can’t plug into Google Translate, but he can translate it for you with no problem. He's literally a better resource than the Internet.”

Both his remarkable scientific achievements and the impressive work carried on by those under his mentorship have shaped Dr. Bauer's legacy.

Famed journalist Margaret Fuller once said, "If you have knowledge, let others light their candles in it." Dr. Bauer has been lighting others’ candles for nearly four decades, in ways that resonate deeply.

“Someone with the level of productivity he has could easily become arrogant, or make you feel that you aren’t worthy of his time,” Dr. Jackman added. “But Aaron is not like that at all.”

Dr. Bauer is accessible and attentive, taking any idea or question posed to him with sincerity, no matter who it came from. He is prompt and incredibly comprehensive in his feedback. Perhaps most important, he is funny, energetic and enthusiastic. Any student entering his lab who might have felt intimidated by his academic stature left after the first day feeling invigorated instead.

“That enthusiasm is infectious,” Patton said. “It is difficult to be around Dr. Bauer and not develop excitement about this field. You may start off with a passing interest, but you walk away with a passion.”

There is unlikely a herpetologist in the world who would argue in describing Dr. Bauer’s legacy by his scientific achievements. Humans possess a far better understanding of reptiles because of his contributions, and the reptiles he has studied—particularly endangered species—have been the true beneficiaries of his life’s work. But for those under his tutelage, that doesn’t paint the whole picture.

“It feels a little silly to look at his achievements and say his students are his legacy, but it’s true,” Dr. Stanley said. “It’s all of the above: the discoveries, the publications—his whole body of work. That includes the continued work of his students. It’s a real tribute to his teaching and mentorship.”

“Hopefully people will continue to cite the things I publish, but eventually they will become old news,” Dr. Bauer said. “But, while there is nobody who does the exact same type of work I do, everything I am interested in is being worked on by these former students. Not only are they pursuing these areas, but they are also taking leadership positions and still interacting with each other.

I get to see them for the first time when they are just starting to have these incredible ideas but still have a lot to learn. By the time they leave, they are leading their field.”

One of his former students just described his 99th and 100th species of Indian gecko. Another has become what Dr. Bauer calls “the world expert” in a large group of snakes with knife-like teeth. Still others, like Dr. Stanley and his micro-CT scanning, are renowned for a technique. Bauer Lab alumni have gone to careers studying skinks, Australian and South American frogs, Asian snakes, reptile specimens found in amber and a “vast majority” of the 40 families of lizards, including, of course, geckos. Many who haven’t remained in herpetology pursued similar work in other zoological branches, researching weaver birds, insects and marsupials.

All of their successes are further inspiration to current students like Nicolau, who intends to pursue his PhD in South Africa and, like his predecessors, continue collaborating with Dr. Bauer.

Those successes are also why that photo taken at the 2024 World Congress of Herpetology in Borneo—and others like it—is a source of pride for Dr. Bauer. It is an opportunity to see a large number of his students together and witness firsthand their continued enthusiasm for the field. It is also personal; these are not just students, colleagues and collaborators, but also friends.

“Seeing everyone together makes me incredibly proud and always reminds me that I can't imagine a job I would have ever preferred more than this one.”