Voyager 2 Confirmed the Existence of Neptune's Rings. Years Prior, Villanova University Research Discovered the Evidence

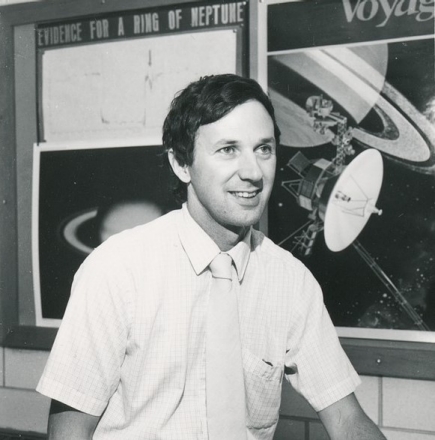

Dr. Guinan sits in front of his research team's poster displaying evidence for a ring around Neptune in 1982. A poster of the Voyager missions hangs adjacent, foreshadowing Voyager 2's photographic confirmation of the planet's ring system in 1989.

Ed Guinan, PhD, ‘64 CLAS was despondent. He didn’t know for sure when his strip chart recorder – which contained crucial, continuous data from a once-in-a-lifetime celestial event – had gone missing, but he knew for sure he and his doctoral thesis were in big trouble.

Dr. Guinan, then in the final phase of attaining that title, surmised they had been confiscated only days prior, by Soviet authorities searching his bag in Moscow. After all, to protect the roll of data, he had wrapped a TIME Magazine – a banned American publication – around it. Now, it was gone. And this became perhaps the most harrowing moment in an unfathomably harrowing series of adventures for the young astronomer in the summer of 1968.

More than a month prior, Dr. Guinan began his journey from Philadelphia to New Zealand’s Mount John University Observatory to conduct research for his thesis. In early April, a very bright star known as BD -17° 4388 was set to pass behind, or be occulted by, the planet Neptune. This occultation would allow astronomers to observe and capture data on the dimming and brightening of the star’s light as it traversed behind the icy planet. By doing so, important new information could be learned about Neptune. That was Guinan’s objective, and an occultation with the planet and a star this bright would not happen again in his lifetime.

It had already been a bumpy road – or in this case, sea – by the time Dr. Guinan arrived in New Zealand. Traveling through the South Pacific en route, he ran out of money and had to work briefly on a Hawaiian pineapple farm to secure funds; a harbinger of the worse luck and struggles that awaited him later in his trip around the world as he returned home.

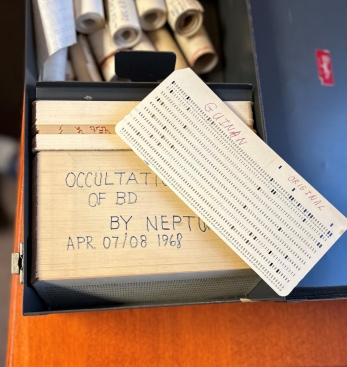

Dr. Guinan's computer punch cards from the occulation of Neptune in 1968 were meant only to be backup data to his strip chart. More than a decade later, they proved to be crucial in showing preliminary evidence of a potential ring around Neptune.

The occultation occurred on April 7, 1968, a clear evening despite a threat of cloud cover. Armed with the chart recorder, which continuously recorded the data, and backup computer punch cards, which recorded data only every several seconds, he got to work. He and fellow researcher Scott Shaw were observing using a small telescope, and at times even their naked eyes.

“It was too cool not to,” Dr. Guinan said. “The chart recorder was running a continuous record of the brightness and time, and the cards were punching. I took the time to look in. Right then, I saw a flashing light and the chart recorder went berserk.”

When it was done, Dr. Guinan was left with thick roll of data to be analyzed back home and roughly 700 computer cards as a lower-value backup, just in case. He was particularly excited about that flash – or scintillation – of light he saw after the star passed behind the planet and was looking forward to piecing together what it may have been for his thesis.

He sent the cards back home by ship in his larger luggage and kept the most valuable data on his person as he prepared for a month-long journey to Philadelphia due west. He couldn’t afford to lose it.

For a while, he didn’t. Not in Cambodia, where he was robbed and taken captive for a week while visiting Angkor Wat, only narrowly escaping. Not in a then-volatile Indonesia, war-torn Vietnam, or trekking through India without money.

But at some point in Russia, perhaps while he was recovering from an acute illness or selling his blue jeans and Villanova t-shirt for travel money, they were taken.

“I had a lot going on, but I was careful with them,” Dr. Guinan recalled. “Maybe it was because of the magazine, or maybe just because the strip charts were scientific-looking pieces of paper. All I knew was it was gone and the hotel knew nothing about it. I was very upset.”

Even more so when he returned home to find his shipped luggage, including his backup data, took on some water. He was able to complete his thesis by pivoting and looking at Neptune’s diameter and atmosphere, but he felt like so much was lost with his missing chart record. The following year, when he started teaching at Villanova University, he threw the once water-warped computer cards in a drawer.

Over the ensuing decade, Dr. Guinan excelled in his young academic career at Villanova. He published research papers by the dozens, made significant discoveries and continued his Indiana Jones-like adventures, studying eclipses from the jungles of Thailand and building observatories while dodging scorpions in Iran. He became a renowned astronomer, a bright spot for the University and the field.

The computer cards stayed in the dark.

♆ ♆ ♆

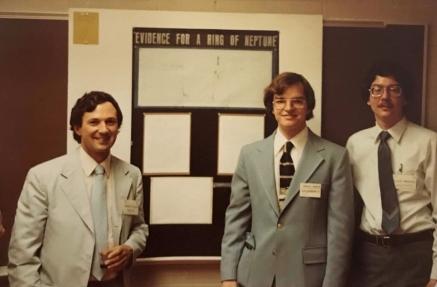

Astronomy student Craig Harris (center) proudly stands in front of his poster presentation at the 1982 American Astronomical Society Meeting, flanked by faculty researchers Dr. Guinan (left) and Dr. Maloney.

Craig Harris ‘82 CLAS was eager. Eager to be involved, eager to learn and eager to be an astronomer. When he approached his Villanova professor in the summer of 1981 looking for a project on which to work, that professor – Dr. Guinan – had an idea.

In 1977, researchers had found strong evidence the planet Uranus contained a series of rings, and they did so by observing disappearances of light during an occultation. Dr. Guinan had long wondered if perhaps Neptune also had rings. He had recalled that similar dimming in 1968, but figured there was no way the data on the backup computer cards was robust enough to show it.

Yet, on a whim, he brought them out, dusted off the box, and gave them to Harris, who he described as a quiet yet passionate student. Here’s your summer project, kid.

“I had been trying for a couple years to get a student interested in doing that,” Dr. Guinan said in a 1982 syndicated newspaper story.

Harris got to work, tediously analyzing the hundreds of hole-punched cards. The summer project became an all-the-time project. Harris was at it for months, fighting through not only a hefty class schedule, but also a case of chickenpox as he went through each and every card, at times needing to hand feed them into the IBM card reader machine due to their damage.

Around Thanksgiving, he had completed the analysis and began to plot the data, graphing the time passed relative to the luminosity of the occulting star.

“Since we knew that Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus have rings, we jokingly said that maybe we'll discover a ring [around Neptune],” Harris recalled in a later issue of Villanova’s The Spires magazine.

What the graph showed astounded Guinan. It clearly indicated a second, brief dimming of light from the star after it had already passed behind Neptune. This dimming, which was by about 30 percent, could have been caused by a number of variables, such as clouds, contrails of a plane or even a celestial body like a moon orbiting Neptune. But Guinan remembered it was a clear night with no apparent clouds. He observed the dimming with his naked eye. At this point, he was cautiously optimistic they had something.

Neptune, he thought, might also have a ring.

♆ ♆ ♆

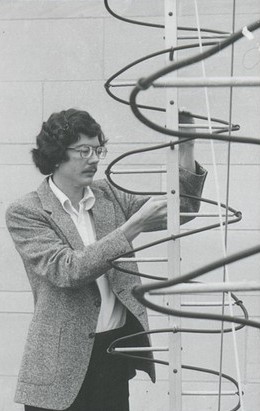

Dr. Maloney, seen inspecting radio astronomy equipment, was originally hired at Villanova due to his background in the field. His study of occultations of radio sources by the moon helped him find a plausible geometry of a ring around Neptune.

Frank Maloney, PhD, was meticulous. He always was with his research, but perhaps a little more so with this project. His colleague, Dr. Guinan, had just asked for his assistance. One of their students, he said, had graphed data from 700 warped computer cards that displayed some interesting phenomena related to a second dimming of light during an occultation of Neptune. They thought it could potentially mean the planet had a ring, but needed to reaffirm how that could be so with geometry.

Dr. Maloney was the man for the job.

He had been an astronomer since he was a little boy. “Ever since my cousin showed me Jupiter and Saturn with his little telescope,” he said. That was all it took.

Dr. Maloney convinced his parents in 1963 to buy him his own telescope that Christmas, and he later won a grant at the local science fair, earning a trip to San Francisco’s International Science Fair all the way from his small hometown in South Carolina.

In college, he studied physics because his school did not have an astronomy program. In fact, as a student, he was the only astronomer on campus and was asked to run the observatory because nobody else knew how to operate the telescope. The astronomy he couldn’t learn in school, he learned from his neighbor, a skilled amateur astronomer himself.

“I’d ride my bike over to his house and he’d have his big telescope out there on the pavement,” Dr. Maloney said.

Dr. Maloney did eventually formally study the field as a graduate student. He became interested in radio astronomy – a way to use radio waves to study celestial objects. It was the perfect marriage of his backgrounds in astronomy and physics.

In 1977, through a mutual connection, Dr. Maloney learned longtime Villanova astronomer George P. McCook, PhD, for whom the main observatory on campus is named, was looking for someone who knew radio astronomy instrumentation.

“I came here on a two-year temporary and they found they couldn’t get rid of me,” Dr. Maloney joked. “I hope I haven’t overstayed my welcome.”

He quickly developed a reputation at Villanova as a talented and scrupulous researcher. At 29, he was named project coordinator by two dozen peers on a special NASA Ames Research Center Project to devise a way to detect potential radio signals from extraterrestrial beings. Later, he and Dr. Guinan observed strange behavior between two binary stars, and his analysis was considered so sound that the astronomical community conceded that perhaps he had found an exception to Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Naturally, when Dr. Guinan needed a meticulous astronomer and physicist to prove that the second dimming could, scientifically, mean a ring around Neptune, there was nobody else he had in mind.

“Frank is very good at celestial dynamics,” Dr. Guinan said. “He’s very rigid, very careful with his science. In a case like this, we needed somebody that careful.”

He jumped right in.

“I was doing work at that time looking at occultations of radio sources by the moon, so I was familiar with one thing getting in the way of another,” Dr. Maloney said. “I also had some computer skills by which I could image what Neptune and the track of the star would have looked like. How do you reconcile that there's a disappearance on one side, but not so much of a disappearance on the other? I was looking to find a geometry that matched the disappearance – trying to figure out how to have a ring.”

Then it hit him.

“It's because the ring is inclined.”

♆ ♆ ♆

Dr. Maloney (left), Dr. Guinan (center) and student researcher Craig Harris discuss their findings with a reporter during an unexpected TV interview at the 1982 American Astronomical Society Meeting.

In February 1982, after a series of re-checks by Dr. Maloney and Dr. Guinan, the team had put together an abstract titled “Evidence for a Ring System of Neptune.” They were to present a poster at the annual American Astronomical Society Meeting in Troy, N.Y. that June.

When they arrived at the conference in their flashy summer sport coats, they were greeted by an unexpected surprise. A media frenzy awaited them, and they were buzzing over the discovery.

“We were not expecting it and we were not ready for that kind of stuff,” Dr. Guinan said. “We never had interviews, never had television or media coverage of the work we did. We didn't think it was all that important because it was a tentative result, and we were nervous.”

There was another small problem: Dr. Guinan, aside from this project, mostly studied stars at that point in his career, not planets.

“And radio astronomy is mostly outside the solar system,” Dr. Maloney said. “There is some planetary radio astronomy, but that’s not what I studied.”

The New York Times, alongside national television networks and other high-profile media outlets, were interested in not only their research, but Neptune itself. From a planetary standpoint, the two professors had little to offer.

They did what anyone would.

“Frank went to the library that night to get some books on planets so we could study up,” Dr. Guinan said. “I got us a bottle of bourbon.”

During the interviews the following days, they were intentional in their language.

“We downplayed it,” Dr. Maloney said. “I didn’t want claim discovery, because that can backfire on you. We were very cautious.”

Well, the professors were at least. Harris perhaps was a little overzealous.

“We are on live TV, all three of us together, and all the sudden Craig steps up and says, ‘Neptune has two rings!’” Dr. Guinan said with a laugh. “I was stepping on his foot, kicking him to stop.”

Dr. Guinan and Dr. Maloney were struck by the enthusiasm the normally reserved student displayed at the conference. They recalled that it was impossible to get him to leave the poster, and the confidence and excitement in how he spoke about it.

The media attention stemming from the poster presentation was robust. In addition to stories in The New York Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer, newspapers across the country published syndicated stories for their own publications. The live TV segment reached a national audience, and Harris’ own cousins heard of the research from a radio report in Omaha, Neb.

All of the stories ended in a similar manner: the science looks great. We’ll know for sure in seven years if Voyager 2 reaches Neptune and sees any rings.

If not, “maybe they will have forgotten about us,” Dr. Guinan said at the time.

♆ ♆ ♆

Dr. Guinan (left) and Dr. Maloney have together been mainstays of Villanova's Department of Astrophysics and Planetary Science for the last five decades.

On August 26, 1989, Voyager 2, hurtling through space roughly 2.9 billion miles from Earth, transmitted the first images of Neptune back home, the day after its flyover of the planet. The images showed two main rings, 33,000 and 39,000 miles away from its icy surface, and an additional two faint rings orbiting the giant.

The ring system was indeed slightly inclined, and also segmented – both of which could have caused the dimming of light on one side. Dr. Maloney’s geometry was correct.

“I was really happy about that,” Dr. Maloney said. “It was a fulfilling moment.”

Voyager 2 had technically discovered the rings, whereas the Villanova team presented the first evidence of their potential existence. A matter of semantics, perhaps, but nonetheless the images marked a breakthrough in an extremely successful – and still ongoing – program that sent hard evidence back to Earth of what the Villanova three, and subsequent researchers, had hoped it would.

“The Voyager 1 and 2 missions have done, and still do, amazing things,” Dr. Guinan said, noting they have since left the solar system and are exploring interstellar space. “With respect to planetary information, it was incredibly important, as they were the first to explore the giant outer planets.”

As quickly as it built up, the frenzy around the original research findings from Dr. Guinan, Dr. Maloney and Harris waned. Research can tend to build upon itself, and in the case of Neptune’s rings, Voyager 2’s findings were like the flashy skyscraper atop the invisible foundation set years before. Work, and life, moved on. The team never forgot their contributions, but it was no longer at the forefront.

Dr. Guinan, who is now inching closer to 60 years teaching at Villanova, spent decades studying everything from stellar astrophysics to interstellar space travel potential, astrobiology (yes, you can grow beer hops in Martian soil) and now, his most recent obsession, habitable exoplanets. More than 800 publications have his name on them, and thousands of students have been able to work alongside him and reap the benefits of his invaluable experience and knowledge of the cosmos. There is often a line of them waiting for him outside his office door. Truly the Indiana Jones of astronomy.

Dr. Maloney, himself nearing 50 years in the department, sits in the office adjacent to Dr. Guinan’s on the fourth floor of the Mendel Science Center. He is heavily involved with both astronomy and planetary science majors and those interested in the field from other disciplines and has devised numerous creative ways to engage Villanova students in astronomy. From developing various web applications, to organizing special events like last spring’s Great North American Eclipse watch, he attempts to create avenues for students to explore space in ways that he did not have as an undergraduate. Recently, he has taken an interest in the concept of timekeeping and calendar, both from a historical and practical standpoint. He includes these themes in a course in which he discusses the fundamental connection between astronomy and our lives.

Harris did not work in astronomy, but he always reveled in it. Six years after Voyager 2 passed Neptune, Harris opened a pizza and ice cream shop in the small town of Niwot, Col. The family shop cemented itself as a community staple over the years. He held movie nights, stayed open late for couples on first dates, and even hosted a wedding. He would allow customers to look through a telescope he kept at the restaurant, and of course would tell anyone that would listen about his work on a certain breakthrough research project.

“He was very proud of this accomplishment,” his son, Craig Harris, said. “It was something that solidified his love for astronomy, which he continued to pass on to as many people as possible.”

In 2022, Harris tragically passed away in a car accident near his home. At the time of his passing, he was in the process of creating a beginner’s guide to using a telescope using images he’d taken with his. His passion for astronomy, forged all those years ago at Villanova, remained with him all that time.

Sometime in the fall of 1989, Dr. Guinan received a postcard in the mail to his office. It was from Harris.

“They found our rings, Doc.”

Just like he had said.