How Children Reason About Disagreements Shaped by School Curriculum

VILLANOVA, Pa. — It is no secret that the earliest years of a child’s life are most important. A critical part of their development is learning what is real and what is not. But when there’s a disagreement, how do they manage competing beliefs? The answer to the question lies in new research from Villanova University assistant professor of Psychological & Brain Sciences, Deena Weisberg, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania and Brown University. They found that the type of curriculum first graders received influenced how children evaluated decisions. The study was recently published in the Journal of Cognition and Development.

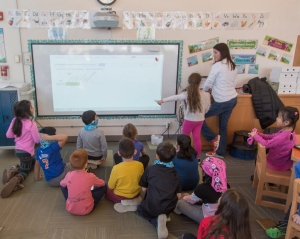

The researchers worked with two groups of first graders: one that received a direct instruction-based curriculum and one that received an inquiry-based curriculum. A direct instruction-based curriculum is one where a student relies heavily on the teacher to obtain factual knowledge about a subject, making the teacher an authoritative source. In an inquiry-based curriculum, children ask questions, make predictions, investigate, and reflect on their knowledge.

“We know that the different methods in which children learn can affect comprehension of objectivity of knowledge, which can affect the ways people disagree,” said Weisberg.

In the study, they asked children about three types of conflicting beliefs: differences based on a matter of fact, a matter of preference or a matter of interpretation.

- Facts are true in an objective sense and can be verified through observations. Ex: The car was made in a factory.

- Preferences are personal and involve attitudes towards an object. Ex. Chevrolet makes the best cars.

- Interpretation combines objective and subjective factors, creating ambiguity and allowing for interpretations to be correct. Ex: The car is parked outside of Macy’s. The store has multiple exits so one person could think that it’s outside the men’s department and another might think it’s outside the women’s department. Without more information, both interpretations can be true.

The study found there was no difference between the groups in relation to preference and interpretation. However, students exposed to an inquiry-based curriculum were more likely to understand disagreement about facts than those who received an instruction-based curriculum. This requires children to recognize that information from others can be false or inconsistent.

“These results show that the way children are taught really matters, even in first grade,” said Weisberg. “The inquiry-based curriculum seemed to be better at encouraging children to understand the objective nature of facts.”