The Long and Winding Road: Pavia v. NCAA [1] and the Future of JUCO

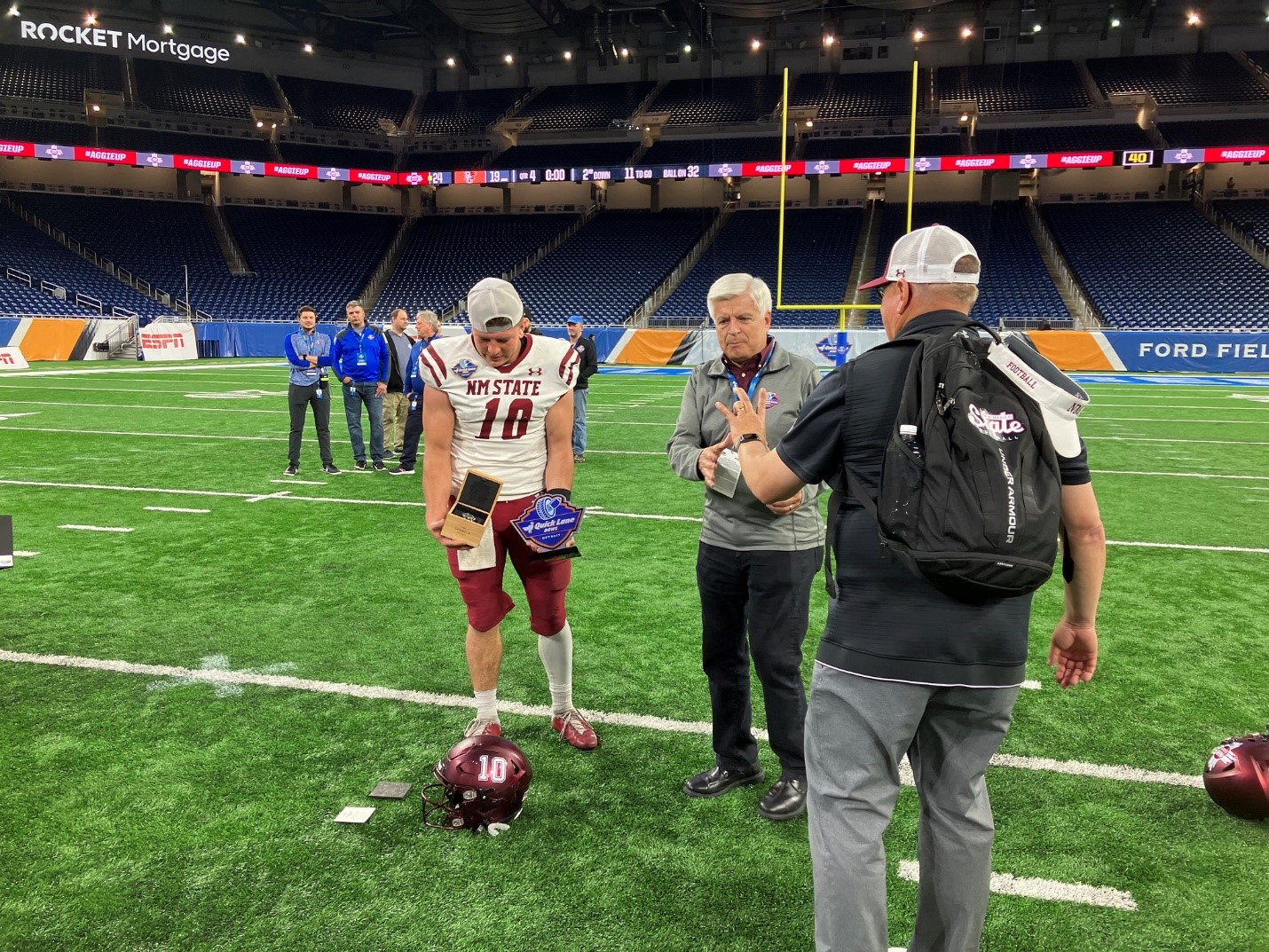

Photo Source: Stephen Ferguson, New Mexico State University QB Diego Pavia with Quick Lane Bowl MVP Awards and Chancellor Dan Arvizu, Flickr (Dec. 31, 2022) (CC-BY 2.0).

By: Ryan Magill* Posted: 04/10/2025

On October 5, 2024, Vanderbilt University (“Vanderbilt”) quarterback (“QB”) Diego Pavia went sixteen-of-twenty for 252 passing yards and two touchdowns as the Commodores beat the number-one ranked University of Alabama (“Alabama”) Crimson Tide for the first time in forty years.[2] Vanderbilt, long considered the football laughingstock of the Southeastern Conference (“SEC”), had its best season in over a decade in 2024.[3] The beating heart of this turnaround was Pavia, a five-foot-ten-inch tall QB who had no offers from Division One football programs upon graduating from high school.[4] Before transferring to New Mexico State University and eventually becoming a graduate student at Vanderbilt, Pavia began his career by winning the 2022 National Junior College Athletic Association (“NJCAA” or “JUCO”) National Championship game with his teammates at the New Mexico Military Institute (“NMMI”).[5] In 2024, with his NCAA eligibility seemingly exhausted, that October win over Alabama looked like it would be the highlight of Pavia’s short stint at Vanderbilt.[6]

However, Pavia clearly had other plans; one month after Vanderbilt’s win over Alabama, Pavia sued the NCAA under the Sherman Antitrust Act in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee.[7] As the basis for his action, Pavia claimed that the NCAA’s decision to include his time at NMMI, a JUCO school, when assessing his playing eligibility “unjustifiably” limited his ability to profit off of his name, image, and likeness (“NIL”).[8] While Pavia was granted an injunction, and the NCAA announced a blanket waiver for 2025–2026 for all former JUCO athletes playing Division One sports, the NCAA’s decision to appeal the injunction renders the issue unresolved.[9] However, with college sports standing at the precipice of full-on commercialization, Pavia’s lawsuit may become the blueprint that changes the relationship between JUCO and the NCAA forever.[10]

Pavia’s (Second) Upset Win: How Pavia beat the NCAA

In Pavia v. NCAA, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee first examined whether the NCAA’s Bylaws on eligibility, agreed to by all member institutions, are subject to Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act.[11] Section 1 requires the plaintiff to demonstrate that the defendant’s agreement(s) “unreasonably restrain trade in the relevant market.”[12] The NCAA argued that Sixth Circuit precedent makes their eligibility rules “non-commercial” in nature and thus beyond antitrust review.[13] However, the District Court sided with Pavia, finding that the emergence of NIL has commercialized NCAA Division One Football, such that eligibility restrictions limit athletes’ abilities to negotiate and enter into commercial NIL deals.[14] The Court quelled the NCAA’s worries that this subjection to the Sherman Antitrust Act would invalidate all of the NCAA’s eligibility requirements, and instead clarified that the Court was only subjecting the JUCO eligibility provision to antitrust review in this instance.[15] Thus, relying on the United States Supreme Court’s decision in NCAA v. Alston,[16] the District Court addressed three elements for reviewing the NCAA’s eligibility rules for an antitrust violation: (1) the plaintiff must demonstrate a “substantial anticompetitive effect;” (2) the defendant must then demonstrate a “procompetitive rationale” for the restraint; and (3) the plaintiff must then demonstrate those procompetitive rationales can be achieved through “less anticompetitive means.”[17]

First, the District Court found that Pavia’s claim proved a substantial anticompetitive effect on college football.[18] The Court determined that the NCAA unfairly punishes athletes financially for not attending Division One schools by counting time spent at a JUCO program the same way as a Division One program, despite the significant NIL market difference.[19] Thus, the current NCAA eligibility rules give Division One football programs a competitive advantage over non-NCAA institutions, such that the District Court found that the current NCAA rules effectuate a substantial anticompetitive effect.[20]

In their “procompetitive rationale” defense of this practice, the NCAA argued that their eligibility rules are about the “college” portion of “college football.”[21] The NCAA said that allowing JUCO athletes to have maximum eligibility hurts the opportunities of younger NCAA athletes and contradicts with the NCAA’s mission of helping athletes progress towards a degree.[22] However, the Court countered the NCAA’s arguments by addressing that other forms of post-secondary education do not eat into an athlete’s NCAA eligibility, even when some of those institutions offer college credit and their athletics programs compete against JUCO programs.[23] The District Court also called the NCAA’s “academic progression” argument into question, since NCAA athletes can transfer an unlimited number of times, despite the fact that transferring multiple times may complicate an athlete’s progression towards their degree.[24]

Finally, the District Court addressed Pavia’s “less restrictive alternative” plan of amending NCAA Bylaws to specifically initiate the eligibility timeframe when an athlete registers “at an NCAA member institution.”[25] The Court found this alternative to be acceptably beneficial to Pavia and similarly situated individuals without harming the NCAA’s overall agenda.[26] Based on its analysis, the Court granted Pavia’s injunction preventing the NCAA from withholding his eligibility to ensure Pavia does not suffer the irreparable harm of missing out on NIL money.[27] Therefore, the Court paved the path for Pavia to play another season with Vanderbilt.[28]

Following the District Court’s ruling, the NCAA adopted a blanket extension of eligibility for all former JUCO athletes competing on NCAA teams for the 2025–26 academic year, but not beyond.[29] Additionally, the NCAA appealed the District Court’s decision to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.[30] Just one month following Pavia’s victory at the district court level, former University of Tennessee men’s baseball player and first baseman, Alberto Osuna, filed a lawsuit seeking nearly identical relief to Pavia’s injunction; Osuna was denied relief on the grounds of an insufficient demonstration of “substantial anticompetitive harm.”[31] While the NCAA may have scored that win, its argument is about to be dismantled by another lawsuit commencing on the other side of the country.[32]

Robbing Peter to Pay Pavia: The House v. NCAA[32][33] Settlement Ups the Ante

On April 7, 2025, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California got closer to rendering a decision concerning the final approval of the terms of the House v. NCAA settlement.[34] This settlement, once approved, will authorize NCAA member schools to directly share up to $20 million in revenue with its student-athletes for the first time.[35] These “House payments” effectively gut the NCAA’s argument that their product is not commercialized.[36] Since the NJCAA lacks any plans to introduce a revenue-sharing program similar to that described in House, the NCAA’s imminent implementation, coupled with the previously mentioned NIL disparity, renders the “substantial anticompetitive effect” issue more prevalent than ever.[37]

The House payments, once approved, will only further support Pavia’s claims against the NCAA, as the SEC is a named defendant alongside the NCAA in House and must therefore abide by its terms, thus requiring schools like Vanderbilt to pay its athletes a portion of the $20 million in athletics revenue offered during the 2025–26 academic year.[38] While Pavia is currently protected by his injunction and the NCAA’s blanket eligibility extension for 2025–26 year, the NCAA must address this issue moving forward or risk being back in court doing the same song and dance with a different JUCO player who was not covered by the 2025–26 extension and is citing the same principles at-issue as Pavia.[39] How the NCAA proceeds in addressing the eligibility issue is anyone’s guess, but Diego Pavia walked the long and winding road when no Division One schools wanted him, and has now forever changed the economic landscape of Division One college football.[40]

*Staff Writer, Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal, J.D. Candidate, May 2026, Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law

[1] See Teresa M. Walker, Vanderbilt Takes Down No. 1 Alabama 40-35 in Historic College Football Victory, AP News (Oct. 5, 2024, 9:34 PM), https://apnews.com/article/alabama-vanderbilt-football-score-upset-ap-poll-a468641fca71fb58f7fc5ed235d48d82 (explaining significance of Vanderbilt’s first-ever win over top-five ranked team and first win over Alabama in forty years).

[2] See Cameron Ohnysty, Who Is SEC Football’s All-Time Winningest Program?, AggiesWire (May 7, 2024, 5:00 AM) https://aggieswire.usatoday.com/story/sports/college/aggies/football/2024/05/07/footballs-winningest-program-football-alabama-football-georgia-football-football-longhorns-football/77764744007/ (discussing Vanderbilt’s dead-last 48.2% all-time SEC football winning percentage); see also Brian Carlson, 2024 Vanderbilt Year in Review, Dore Rep. (Jan. 2, 2025), https://vanderbilt.rivals.com/news/2024-vanderbilt-year-in-review (reporting on Vanderbilt’s successful 2024 season).

[3] See Mark Schlabach, How Vanderbilt Turned to New Mexico State for the Coaches and QB Who Helped Beat Alabama, ESPN (Oct. 8, 2024, 7:00 AM), https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/41671222/vanderbilt-alabama-upset-diego-pavia-clark-lea (explaining how Pavia was overlooked by Division One programs in high school).

[4] See id. (detailing Pavia’s long road to joining Vanderbilt’s football program).

[5] For further discussion of how Pavia addressed his seemingly expiring NCAA eligibility, see infra notes 11–32 and accompanying text.

[6] See Teresa M. Walker, Vanderbilt QB Diego Pavia Sues NCAA Over Eligibility Limits for Former JUCO Players, AP News (Nov. 9, 2024, 9:35 PM), https://apnews.com/article/vanderbilt-diego-pavia-suing-ncaa-541a9dcd33815a9c006ee42dd9f4819b (reporting on Pavia’s filing of lawsuit against NCAA).

[7] See Pavia v. NCAA, No. 3:24-cv-01336, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 228736, at *11 (M.D. Tenn. Dec. 18, 2024) (explaining crux of Pavia’s antitrust claim against NCAA over his inability to negotiate and receive NIL money due to NCAA eligibility rules for former JUCO players).

[8] See Eli Lederman, NCAA Grants Waiver to Ex-JUCO Players While Appealing Pavia Ruling, ESPN (Dec. 23, 2024, 6:39 PM), https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/43131557/ncaa-division-board-grants-waiver-former-juco-players-appealing-diego-pavia-injunction (reporting on NCAA’s decision to grant blanket eligibility waiver for all former JUCO athletes for 2025–26 year while appealing court decision in favor of Pavia).

[9] For further discussion of Pavia’s case against the NCAA, see infra notes 11–32 and accompanying text. For further discussion of the ripple effects of Pavia’s case, see infra notes 34–40 and accompanying text.

[10] See Pavia, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 228736, at *13 (discussing relevant antitrust law).

[11] See id. (“[W]hether the challenged rules unreasonably restrain trade in the relevant market, which they seem to agree is the labor market for college football.”).

[12] See id. at *13–14 (explaining that antitrust law only applies to rules which are “commercial in nature”).

[13] See id. at *15 (“Plaintiff asserts that when the NCAA lifted the restriction on NIL compensation, rules regulating who can play–i.e., who can enter the labor market for NCAA Division I football–became commercial in nature . . . . [t]he Court agrees.”).

[14] See id. at *16 (explaining that NCAA retains power to impose eligibility requirements, but that Pavia had sufficiently demonstrated need to review JUCO eligibility requirement).

[15] NCAA v. Alston, 594 U.S. 69 (2021).

[16] See Pavia, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 228736, at *17–18 (detailing standards proffered by Supreme Court in Alston regarding how to analyze antitrust claims brought against NCAA).

[17] For further discussion of how the Court sided with Pavia’s claims in finding the first Alston standard met, see infra notes 19–20 and accompanying text.

[18] See Pavia, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 228736, at *21–22 (explaining unfair and different realities for NCAA Division One and JUCO programs, despite identical treatment regarding eligibility).

[19] See id. at *25 (“[T]he Court finds Plaintiff has shown a likelihood that that the challenged restraints have a substantial anticompetitive effect in the labor market for college football.”).

[20] For further discussion of how the Court rejected the NCAA’s arguments in finding the second Alston standard was not met, see infra notes 22–24 and accompanying text.

[21] See Pavia, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 228736, at *25–28 (describing NCAA’s “procompetitive rationale” defenses against Pavia’s assertions that NCAA’s JUCO eligibility rules have “substantial anticompetitive effect”).

[22] See id. at *28 (“The NCAA eligibility rules allow other forms of post-secondary education and athletic competition without it ‘counting’ against eligibility.”).

[23] See id. at *30–31 (considering NCAA’s argument regarding academics in light of recent bylaw amendment that permits unlimited transfers, even when it poses significant academic challenges).

[24] See id. at *31–32 (analyzing Pavia’s “less restrictive alternative” for NCAA eligibility rules in light of Pavia’s “substantial anticompetitive effect” defense and NCAA’s “procompetitive rationale” defense).

[25] See id. at *32 (“Plaintiff's proposed alternative eliminates the anticompetitive harms discussed above while appearing to satisfy many of the rationales advanced by the NCAA.”).

[26] See id. at *33–36 (detailing reasons for acceptance of Pavia’s injunction for extended eligibility).

[27] See Brad Wakai, Diego Pavia Officially Announces His Return to Vanderbilt for 2025 Season, Sports Illustrated (Dec. 29, 2024), https://www.si.com/college/vanderbilt/football/diego-pavia-officially-announces-his-return-vanderbilt-2025-season (reporting on Pavia’s decision to continue playing for Vanderbilt in 2025–26 season).

[28] See Lederman, supra note 9 (reporting on NCAA blanket waiver of eligibility for former JUCO athletes for 2025–26 year).

[29] See id. (discussing NCAA’s appeal made to Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals over Pavia ruling).

[30] See Michael McCann, Tennessee Baseball Player Takes on NCAA in Latest Eligibility Case, Sportico (Feb. 14, 2025, 10:00 AM), https://www.sportico.com/law/analysis/2025/alberto-osuna-lawsuit-court-ruling-1234828270/ (reporting on second JUCO athlete lawsuit filed in Tennessee and its opposite outcome to Pavia’s lawsuit based on that athlete’s eligibility not falling within NCAA’s 2025–26 blanket eligibility waiver for former JUCO athletes).

[31] For further discussion of the impact of the House settlement on future JUCO eligibility cases against the NCAA, see infra notes 34–40 and accompanying text.

[32] House v. NCAA, 545 F. Supp. 3d 804 (N.D. Cal. 2021)

[33] See Justin Williams, House v. NCAA Settlement Granted Preliminary Approval, Bringing New Financial Model Closer, The Athletic (Oct. 7, 2024), https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/5826004/2024/10/07/house-ncaa-settlement-approval-claudia-wilken/ (reporting on status of House settlement after preliminary approval was granted); see also Becky Sullivan, Landmark Day for College Sports As Judge Holds Final Hearing on Major NCAA Settlement, NPR (Apr. 7, 2025, 8:21 PM), https://www.npr.org/2025/04/07/nx-s1-5354232/paying-college-athletes-ncaa-legal-settlement (providing updates on House settlement status after hearing held on April 7, 2025).

[34] See Pl.’s Mot. for Prelim. Settlement Approval at 8, In re College Athlete NIL Litigation, No. 4:20-CV-0319, 2924 WL 5361639 (N.D. Cal. July 26, 2024) [hereinafter Settlement] (describing revenue-sharing model of up to $20 million annually for eligible student-athletes). The Settlement’s revenue-sharing model will result in billions being paid out directly to student-athletes at all sixty-nine schools in the Power Five conferences, who are named defendants in the lawsuit. See id. (“For all Power Five Schools, that would allow for additional spending of up to $1.6 billion for 2025-26, growing to $2.3 billion in 2034-35, and totaling $19.4 billion for the 10-year period of the Injunctive Settlement.”). The Settlement also allows all Division One schools, not just those in the Power Five conferences, to directly compensate their athletes. See id. (“[A]ll 363 Division I schools will be able to provide benefits to student-athletes up to the Pool amount every year.”)

[35] See Michael McCann, Congress May Have to Settle NCAA Athlete Eligibility Issue, Sportico (Mar. 10, 2025, 5:55 AM), https://www.sportico.com/law/analysis/2025/ncaa-congress-eligiblity-cases-1234842374/ (exploring effect of House settlement on NCAA eligibility rules in light of Pavia lawsuit and others).

[36] See generally Settlement, supra note 35 (containing applicable terms of House settlement regarding revenue-sharing, for which NJCAA is not subject to because it is separate entity from NCAA).

[37] See Seth Emerson, Georgia, SEC Schools Expected to Pay Football Athletes About 75 Percent of Revenue Sharing, The Athletic (Feb. 25, 2025), https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/6159981/2025/02/25/college-football-revenue-sharing-georgia-sec/ (reporting on how SEC schools intend to engage in revenue-sharing practices in 2025–26 academic year). For further discussion of how Vanderbilt is a member of the SEC, see supra note 3 and accompanying text.

[38] See Lederman, supra note 9 (reporting on Pavia’s ensured eligibility stemming from injunction granted for 2025–26 year); see also McCann, supra note 36 (acknowledging one judge’s indication that eligibility issue will result in more litigation in near future).

[39] For further discussion of how the NCAA could proceed in response to litigation over its eligibility, see supra note 36 and accompanying text. For further discussion of how Pavia went from undesirable to undeniable in college football, see supra note 5 and accompanying text.