The Force

of Nature

of Nature

How this biology research

created connections that stick

Alyssa Stark, PhD, has quite an exotic trip planned this summer: She’ll spend 14 days in the treetops of a tropical forest in Panama. Supported by a National Science Foundation grant, she will observe and collect over 50 species of tropical arboreal ants–learning more about how they manage to keep their footing despite temperatures as high as 123°F underfoot.

Without any wings, these tiny daredevils don’t have a backup plan–if they slip and fall, they will plummet more than 100 feet to the forest floor. How do they meet these challenges? When do they fail and why? Dr. Stark is on a mission to answer those questions with the help of six Villanova undergraduates; a master’s student; a postdoctoral associate; and her co-principal investigator, Steve Yanoviak, PhD, of the University of Louisville.

“By testing multiple species, we can investigate if and how different adhesive strategies work for ants that have different roles in their environment,” says Dr. Stark, who joined Villanova in 2017 as an assistant professor of Biology. “This will give us insights about how ant adhesion works and some key components of its success.” Next, they will share those insights with material scientists and engineers who will build the first ant-inspired synthetic adhesive prototypes–a potentially more versatile, reusable adhesive.

This project is just one snapshot of the kind of intensive, collaborative scholarly work that comes out of Dr. Stark’s research lab–whether she’s studying ants, geckos or sea urchins, in their natural habitat or in the Mendel Science Center. “I see myself as the biologist on the ground–or in some cases, climbing the trees or digging in the tide pools–looking at the very, very fundamentals of what organisms do, and why and how they do it,” she says. “Then I bring that knowledge to the materials people who can use that information to make something.”

While it may seem like a niche topic, Dr. Stark’s research has had quite an expansive reach. Throughout her career, she’s published papers in more than 30 academic journals; worked with more than 70 undergraduate and graduate students in her lab; partnered with experts in biology, engineering, education and business; and traveled thousands of miles to conduct on-site research, from the rainforest canopy in Barro Colorado Island, Panama, to the tide pools in Bodega Bay, Calif.

“There is always something new to learn, question and study,” Dr. Stark says. “Nature has a truly unlimited supply of inspiration, and I like to have my hands in all of it.”

Inspired by Nature’s Design

Dr. Stark’s specialty is called functional morphology, which means she investigates the relationships between the structure of an organism and how its various parts function. Specifically, she looks at adhesion in ants, geckos and, more recently, sea urchins.

“I love adhesion challenges, exploring the types of adhesives in nature that can work in really difficult, extreme environments,” she says. In addition to her NSF-funded research on tropical arboreal ants, her recent work has studied how geckos can inspire synthetic adhesives that can work in wet and humid conditions, and how sea urchins adhere to different types of rock despite being pummeled by crashing waves.

“I never thought I would study any of these things,” Dr. Stark says. “And yet there is a common theme: They all must maintain function to survive in their complex and challenging environments. I think there’s a lot we can learn from nature’s design.”

It’s more than just a philosophy for Dr. Stark–it’s a lens through which she sees her work. The field is called biomimicry: an approach to innovation that seeks inspiration and solutions to human challenges by emulating nature’s time-tested processes and systems. “Nature is like a business. It has to deal with lots of different dynamics and changes and continue to innovate and evolve to be successful,” she says. “I’ve always had the goal of keeping biomimicry in my work in some capacity, and, for me, that’s through collaboration.”

While some of those collaborations involved working with companies that make commercially available bio-inspired adhesives, the insights from her research extend far beyond product design.

In addition to publishing groundbreaking findings on ant, gecko and sea urchin adhesion, she’s co-authored papers for academic business journals on how biomimicry can inform entrepreneurship scholarship and partnered with childhood educators in developing lesson plans to use nature as a way to teach engineering to adolescents. In 2020, she even penned a piece for The Wall Street Journal on lessons about adaptation that businesses can learn from nature.

“With the help of people from multiple fields, such as chemistry, physics, engineering, material science, even business, education and art, I can investigate my questions more deeply and apply them more broadly,” Dr. Stark says. “I think that is the direction science is going, and I am excited to be a part of it.”

“ I love adhesion challenges, exploring the types of adhesives in nature than can work in really difficult, extreme environments. ”

- Alyssa Stark, PhD

DID YOU KNOW?

Ross A. Lee, PhD, a professor of practice in Sustainable Engineering, has taught a graduate course on biomimicry at Villanova since 2015. He focuses on how the next generation of engineers can use observations from nature to provide sustainable solutions for everyday needs. At the Middle Atlantic American Society for Engineering Education Spring 2021 Conference, Dr. Lee and four of his former students presented a paper about the significant impact the course had has on changing the mindset of past students.

New Dimensions to Research

Working with so many experts and academics outside her field, Dr. Stark has also found new ways to partner with other biologists. One of her most fruitful research collaborations in Villanova’s Biology Department began before she even joined the faculty. Wrapping up her job interview, Biology Professor Michael P. Russell, PhD, asked if she had any questions for him. Her answer was unexpected. Dr. Stark asked if he had given much thought to the structure of tube feet in sea urchins, a creature he’s been studying for four decades.

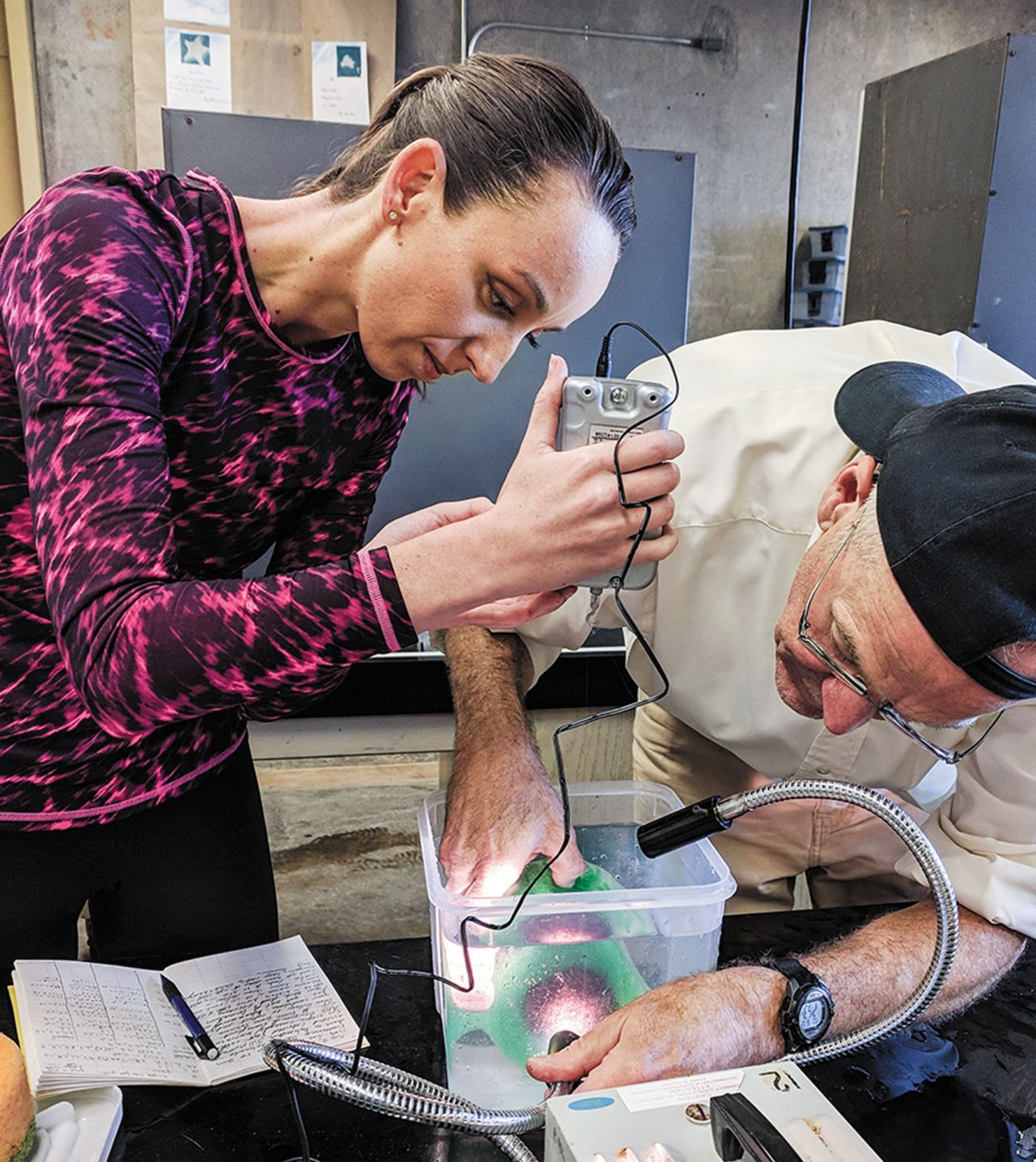

Within months, she and Dr. Russell were sampling sea urchins from tide pools on the California coast. “I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to work with sea urchins without him–he has this amazing working knowledge of the ecology of sea urchins and the marine intertidal zone,” Dr. Stark says. “He’s a marine biologist and ecologist, and I bring biomechanics and adhesion to the equation.”

Over the last five years, they’ve collaborated on research, co-advised students, published two papers and led numerous research seminars together. “I've been working on sea urchins since the 1980s,” says Dr. Russell. “I thought I was the expert–and some people think I am, but my work with Alyssa has taught me so much more about the organisms I know so well. Our collaboration has added different dimensions to the things that I’ve been looking at for a long time, and that’s really energizing.”

For Dr. Stark, it’s a new frontier. “In terms of what direction my research is taking, the new interesting, big questions are actually about sea urchins,” she says. That’s because, like the geckos and ants she studies, sea urchins have special adhesive qualities.

“Imagine if you had something that was strong like super glue, but temporary. That’s just one example of the biomimetic potential that these creatures have,” says Austin Garner, PhD, a postdoctoral teaching fellow in Biology. “As we learn more about these natural systems, we are able to add more and more to the body of literature and knowledge–which can serve as inspiration for new innovations and new perspectives.”

Dr. Garner’s previous research focused on the interactions between form, function and environment in geckos and similar reptiles called anoles. Since joining Villanova in August 2021, he’s been studying the form and function of sea urchin adhesion in the lab of Dr. Stark and in collaboration with Dr. Russell.

It’s not Dr. Garner’s first time in the lab with Dr. Stark–he was actually one of the undergraduates who helped carry out her PhD dissertation work at the University of Akron, looking at how geckos stick underwater. “At the time, I knew that I wanted to be an animal biologist, I just didn’t know what I wanted to do,” Dr. Garner says. “Before that, I had no idea research was an option–but I became instantly hooked.”

Dr. Stark encouraged him to take that enthusiasm and run with it, which he did–all the way to first-author publication in a national journal as a senior undergraduate student. “That wouldn’t have been possible without Dr. Stark’s mentorship,” Dr. Garner says. “She really never stopped mentoring me and encouraging me.” He later decided to pursue a PhD in the same lab that she did, working on similar topics in a different way.

When Dr. Garner had finished his PhD, he found a postdoctoral teaching fellowship perfectly suited to his research and skill set–and it happened to be in Villanova’s Biology Department. “It was a full-circle moment,” he says. “It’s a really unique postdoctoral position because it allows me to do many of the things that faculty members get to do, which is be involved in research, teaching and service as well.”

Although Dr. Garner’s fellowship comes to an end in August 2022, he plans to continue working with Dr. Stark and Dr. Russell when he joins the faculty at Syracuse University this fall as an assistant professor of Integrative Animal Biology.

The three researchers, along with another former postdoctoral fellow, Carla Narvaez, PhD, now at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories, will be applying for a collaborative grant looking at the impact of climate change on three species of sea urchins that typically live along the West Coast.

Passing It On

There are dozens of stories from Villanova students that mirror Dr. Garner’s. As passionate a scientist as Dr. Stark is, she’s perhaps even more animated when talking about sharing that science through teaching and mentorship.

With 10 undergraduates, a master’s student and a postdoctoral teaching fellow, her lab has a large student presence. “I love having a big group,” Dr. Stark says. “It provides a community for the students and it works really well with the tiered mentoring approach I use.”

The younger undergraduates who join her lab begin by learning how to run the basic equipment, getting experience with multiple types of organisms, observing how data are collected and how scientific research is done. They check in with Dr. Stark regularly, but most of their day-to-day interactions in the lab are with the senior students she advises.

When Dr. Stark works with these seniors, she mentors them not only in science and designing their own experiments but also in the process of teaching others. They learn valuable skills they’ll need in the lab–mentoring, time management, delegation and collaboration. “I treat my undergraduate students like graduate students–they are a wonderfully untapped resource at most institutions,” she says. “They work on research that’s going to be published, and they spend two to three years in my lab working on at least one project of their own.”

That’s exactly what Bridget Ringenwald ’20 CLAS did. She joined the nascent lab in 2018, the summer after her sophomore year. After training in the basics, she worked with Dr. Stark the following year to design the study that would become her senior thesis: the effect of variable temperature, humidity, and substrate wettability on gecko locomotor performance and behavior. Translation: Whether varying the temperature and humidity would change how Tokay geckos run.

Over the next year and a half, Ringenwald served as the lead researcher of the study, carrying out dozens of trials in the lab. “It really was a great leadership role for me, learning how to organize a study, delegate some of the responsibility to younger students and mentor other students as well,” she says.

“Dr. Stark entrusted me with a big responsibility–and I’m so honored that she did,” says Ringenwald, now in her second year at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. “She was a fantastic mentor and showed me not only how to carry out a study from start to finish but also how to carry myself as a researcher in STEM.”

And it shows in Ringenwald’s curriculum vitae. In January 2020, she presented her thesis research at the annual conference for the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology in Austin, Texas, where she met leading scientists in the field. She completed her thesis in May 2020, earning the Biology Department’s Distinction in Research Award for excellence in independent research. And in April 2021, she published the work as a first author in the Journal of Experimental Zoology.

As extraordinary as these accomplishments are, they’re not uncommon in Dr. Stark’s lab. She’s published seven peer-reviewed publications in national and international journals with 11 undergraduate and graduate students as co-authors–and seven more papers are currently in progress.

“In five years, my students and I have built this really amazing research program together–and in particular, during a very difficult time. I’m so proud of the resilience of our lab and the depth of our research,” Dr. Stark says. “We’re not just jumping from one cool thing to the next, we’re really trying to understand the systems we’re looking at in a deeper way, and every single one of my students has helped with that.” ■

A Different Kind of Homemaker

Villanova researchers make groundbreaking discoveries about sea urchins’ DIY homes

From the moment Biology Professor Michael Russell, PhD, began studying sea urchins in the early 1980s, he’s been fascinated by their living quarters. “When the tide recedes, you’ll see these tiny cavities on the rocky bottom of the tide pools where they live,” he explains. “They look like little condominiums custom-made for the size of each sea urchin.”

For nearly four decades, Dr. Russell wondered: Do they make them?

He certainly wasn’t the first to ask. In the 1830s, scientists first posited that the fit was so precise, the answer had to be yes. “Everyone just assumed that the sea urchins made these pits because all of the literature cited that original research,” he says. “But when you actually look at those papers, there’s not a scintilla of evidence. It’s just a logical argument.”

That all changed in 2018 when Dr. Russell, a postdoctoral fellow and a Villanova undergraduate published the first paper with data to demonstrate that sea urchins do indeed carve out their humble abodes. Based on their calculations, it takes about five years for them to excavate an average-sized pit in medium-grain sandstone.

How? “In the course of feeding, sea urchins scrape the rock surface using their self-sharpening, regenerating teeth, which act as ‘rock picks,’” Dr. Russell says. “This process results in the excavation of pits.”

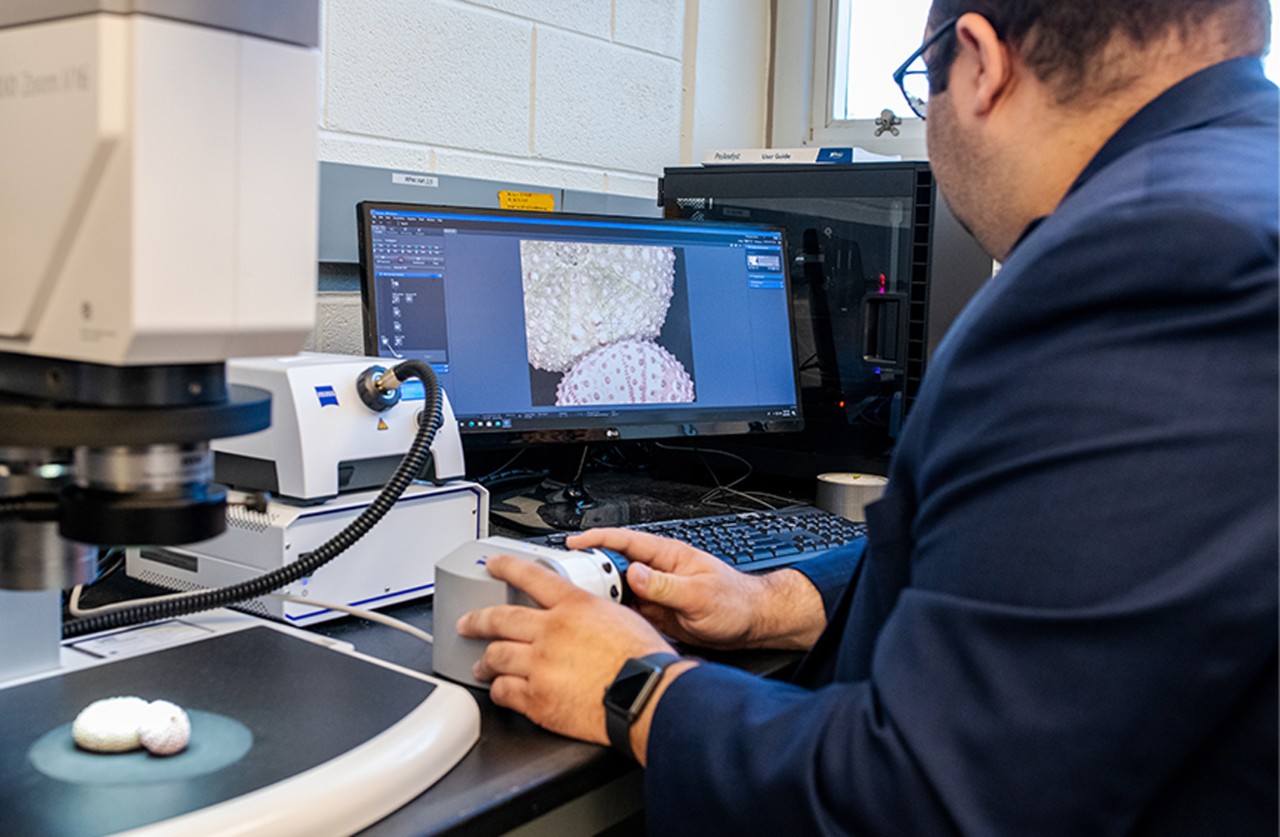

Now he’s digging even deeper into this research with two other colleagues at Villanova—Alyssa Stark, PhD, assistant professor of Biology, and Gang Feng, PhD, an associate professor of Mechanical Engineering and director of the College of Engineering’s High Resolution Microscopy Laboratory. They’re looking to understand more about the composition and function of sea urchin teeth.

Thanks to Dr. Feng’s expertise in highly specialized microscopic instrumentation, he’s able to provide precise data about the material properties of the sea urchin’s teeth—with a level of specificity that’s even smaller than a grain of salt.

“Mother Nature has fine-tuned these materials, and we’re basically just trying to get more information about her design,” Dr. Feng says. So far, they’ve made some discoveries about just how the teeth sharpen themselves. Like a self-sharpening utility blade, the teeth have natural breaking points—and when they break, they leave a fresh sharp edge.

“Unlike the inside of the tooth, which needs to stay strong, the areas of self-sharpening have different material properties,” Dr. Stark explains. “The edges flake off as needed to stay sharp.”

With two papers underway, soon they’ll be able to share these findings which will provide material scientists and engineers with design parameters they can use to create new products and apply this knowledge to synthetics.