Where’s

my stuff?

Villanova experts weigh in on global supply chain

disruptions and potential solutions

The average consumer may not have an expert understanding of how the supply chain functions, but they know that the COVID-19 pandemic has essentially left that chain in pieces. So, how does it work, what’s causing these bottlenecks and what needs to be done to get the supply chain working properly again?

Villanova Magazine turned to three supply chain experts on the Villanova faculty to provide some answers and share their insights on the current crisis.

MEET THE EXPERTS

Kathleen Iacocca, PhD

Associate Professor-NT of Management and Operations, Villanova School of Business

Holding a doctorate in Supply Chain Management, Dr. Iacocca is an expert on supply chain management, business analytics and optimization with a focus on health care industries. Her research and teaching focuses on supply chain management, operations management, total quality management, health care, optimization and pharmaceutical supply chains.

Karl Schmidt

Professor of Practice in Sustainability, College of Engineering

Professor Schmidt began teaching at Villanova when he retired from Johnson & Johnson in 2012. He spent the last two and a half years of a 28-year career with J&J leading the deployment of the company’s global supply chain strategy, as well as developing and leading J&J’s global supply chain risk management framework.

Arthur Hudson

Adjunct Professor, Villanova School of Business and College of Professional Studies

Professor Hudson has more than 40 years of experience working at all levels of operations in service and manufacturing environments at organizations such as Mobil Oil and Tyco Electronics. He is professionally certified through the Association for Supply Chain Management in production and inventory management as well as logistics, transportation and distribution, and supply chain management.

Supply Chain 101

Lately, it seems like “supply chain” has become a part of the everyday lexicon, but what is it?

Contrary to what its name may suggest, it’s not exactly a chain with links that form a straight line, says Kathleen Iacocca, PhD, associate professor-NT of Management and Operations at the Villanova School of Business.

“It’s really more of a web, a network of interconnected suppliers," explains Dr. Iacocca, who holds a doctorate in Supply Chain Management. “If you asked someone to map out their supply chain, it’s messy.”

And supply chains have become more complex as the marketplace has become more globalized. An increasing focus on cost has led many US companies to outsource operations overseas, where suppliers can help reduce product cost because they have lower labor rates, says Karl Schmidt, professor of practice in Sustainability in Villanova’s College of Engineering.

So, in many cases, consumers are relying on a global supply chain—not a domestic one—to deliver their products. “In a nutshell, the global supply chain is the process of how raw materials and components are brought together to produce finished goods and services that are distributed and sold to customers,” Professor Schmidt says.

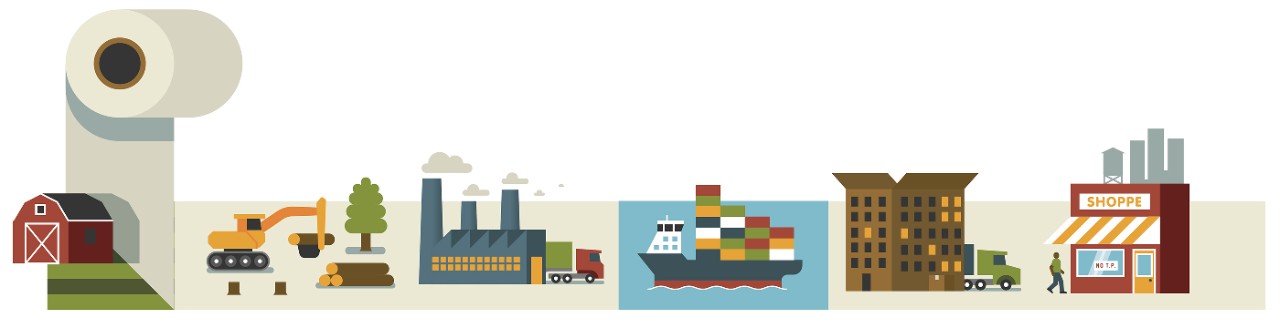

Whether it’s something as seemingly simple as toilet paper or as involved as an automobile, the supply chain for every product involves multiple stages and a coordinated approach using suppliers, manufacturers, distributors and retailers, among many others.

“It’s a very delicate set of events,” explains Arthur Hudson, an adjunct professor who teaches Supply Chain Management in the Villanova School of Business and Villanova’s College of Professional Studies. To illustrate how even one small action or event can upend this fragile process, Professor Hudson calls to mind an all-too-familiar traffic analogy.

Imagine coasting along on a busy highway when a driver ahead hits their brakes. This prompts all the drivers behind them to slow down or even stop—and suddenly, there’s a line of vehicles starting to back up that will inevitably cause a massive traffic jam.

This is exactly what happens when there’s a holdup in some aspect of the supply chain: It can cause a ripple effect that slows down the entire process, or worse, brings it to a screeching halt. Whether it’s sparsely stocked shelves in grocery stores or online orders with lengthy shipping delays, these holdups have become all too familiar over the past two-plus years.

The Perfect Storm

When the pandemic arrived in early 2020, consumer demand for many products took off in a way that couldn’t have been anticipated, wreaking havoc on the supply chain.

“There was a huge surge in demand for some products that we typically expect to stay stable—ventilators and face masks, for example, suddenly skyrocketed; while demand for other products, such as cosmetics or school and office supplies, stayed normal or went down,” Dr. Iacocca says. “It was something that could not have been predicted even a few months ahead of time.”

But COVID-19 didn’t create this crisis—it exacerbated an existing one.

“Before the pandemic, many companies were focused on efficient, lean supply chains, and on having products available just in time for customer demand,” Professor Schmidt explains.

In reality, some time is required to take a product from raw materials to being consumer-ready. Effective forecasting to gauge demand is a crucial piece of the puzzle—so when those forecasted numbers are off, and companies have to make significant adjustments, it takes time for inventory to catch back up to meet those needs.

Add a once-in-a-lifetime global pandemic to an already strained system with tight turnarounds, and it’s a perfect storm.

“The pandemic heavily disrupted all aspects of the supply chain—planning, sourcing, production and delivery from a variety of sources,” Professor Schmidt says. As customers moved to shop online, the demand for products increased—just as many companies were shutting down production, of course.

“And, when we have COVID rolling through the world in different phases, the resulting shutdowns and disruptions it creates affect the supply chain,” says Dr. Iacocca.

The first pandemic-related lockdown went into effect in January 2020, in Wuhan, China, nearly two months before the virus upended every aspect of life in the United States. But given China’s status as “The World’s Factory,” it was inevitable that America would eventually feel the effects, says Dr. Iacocca. China accounted for nearly 30 percent of global manufacturing output in the year before COVID-19 arrived, according to data from the United Nations Statistics Division.

“China shut down first, and there are a lot of suppliers in China, although it took some time to trickle down,” she says, adding that the effects of a particular lockdown-related shortage might not be felt until two or three months later.

Labor shortages compounded the issue, and many ports simply didn't have the manpower to process, unload and transport the influx of durable goods from China. Labor was far from the only factor causing problems, though.

“Factor in logistical impacts from climate change—floods, wildfires, hurricanes, for instance—and this all creates the cascading bottlenecks that we’ve experienced over the past two years,” Professor Schmidt says.

Overcoming any one of these challenges and the kinks it creates in the supply chain would be challenging, but doable, says Dr. Iacocca. “If there were just one factor, it would probably be fine,” she says. “But it’s the multiple stressors that are causing the issues we’re seeing now.”

Dealing with Supply Chain Stressors

Throughout the pandemic, various sets of temporary circumstances—surges and dips in demand, lockdowns here and abroad, a subsequent return to business at less-than-full capacity, increased consumer demand resulting from the COVID stimulus program, for instance—threw supply chains into disarray.

“Eventually, these issues will be resolved, and things should return to something approaching normal,” says Professor Hudson. “The market will also adjust, and in some cases that’s happening now, as companies move to shorten their supply lines by bringing production back to the United States.” (Intel, for example, is beginning to make computer chips in Ohio, amid a global shortage.)

Of course, there are more lingering issues affecting the supply chain, issues that a global pandemic only intensified.

Consider the ongoing shortage of commercial truck drivers, for example. The American Trucking Association estimated a shortfall of more than 60,000 truck drivers before the pandemic, with that number growing to more than 80,000 in the past two years.

It’s not just the transportation industry that’s experiencing these issues—the U.S. has been dealing with staffing shortages in just about every sector, including manufacturing, processing and retail.

Ultimately, each of the variables currently affecting the supply chain equation comes with its own set of issues that need to be addressed. Affected organizations will ultimately find solutions to these issues, says Professor Hudson, “because companies’ ability to do business and their profitability are being adversely impacted by these shortages.”

Likewise, those businesses that don’t work to solve their supply chain issues will lag behind their competitors. “Those companies that are adapting and alleviating the issues are taking market share away from those that have not been able to find solutions,” says Professor Hudson. “There is a solution to every issue, and we need to address these issues earlier, before they become a crisis.”

All that said, companies should get used to dealing with supply chain disruptors, even after the pandemic eventually subsides, adds Dr. Iacocca.

“COVID brought the supply chain to everyone’s attention. But what if a tsunami or earthquake comes along and wipes out a supplier? There are always going to be hurdles to overcome, and suppliers have to be prepared,” she says. “As for the current situation, the most important thing is time. It’s probably going to take maybe another eight months to a year before these issues are resolved, and that’s under the assumption there won’t be any more abnormal events. We’re just going to have to be patient.”

CASE IN POINT

Unraveling the Toilet Paper Shortage

Dominating household discussions and headlines alike, the Great Toilet Paper Shortage of 2020 left shelves bare and consumers scratching their heads about why it suddenly seemed impossible to replenish their rolls. It’s a perfect example of how complex – and delicate – the supply chain is, even for a product as simple as toilet paper.

Trees are grown and cut (or material is recycled) to be turned into pulp, which is then milled into paper, sent to a distributor, packaged at a plant and delivered to retailers before making its way to your bathroom. It’s a multifaceted process with the potential for any number of disruptions at each step along the way. So let’s take a look at just a few plausible explanations to answer the question that was on every one’s mind – where’s my toilet paper?

LANDOWNERS

Landowners plant and grow trees to be used for paper.

POTENTIAL DISRUPTIONS:

• natural disasters (forest fires and mudslides)

• diseased trees

• equipment used to plant and maintain trees may be down due to wait time for repair parts

LOGGERS

Loggers cut and log trees to be milled into wood pulp.

POTENTIAL DISRUPTIONS:

• reduced workforce due to strike and pandemic

• equipment used to plant and maintain trees may be down due to wait time for repair parts

MILL WORKERS

Mill workers run the pulp mill, turning trees into pulp and then into paper.

POTENTIAL DISRUPTIONS:

• reduced workforce due to strikes

• reduced capacity due to social distancing and sterilization efforts in the facility

• delays in maintenance on equipment because parts are unavailable

DISTRIBUTORS

Distributors move the paper from the mills to stores.

POTENTIAL DISRUPTIONS:

• increase in gas prices

• reduced workforce due to strikes

• port staffing shortages

• lack of sufficient room to unload ships because ports are full

• shortage of truck drivers to transport the goods

PACKAGING SUPPLIERS

Packaging suppliers wrap/box the paper.

POTENTIAL DISRUPTIONS:

• raw material delays and shortages

• reduced capacity due to social distancing measures and sterilization efforts in the facility

RETAILERS

Retailers sell the finished toilet paper product to customers.

POTENTIAL DISRUPTIONS:

• unanticipated levels of demand from panic buying

• unable to get product because of disruptions in other parts of the supply chain