United in

Purpose

Purpose

Villanova’s approach to COVID-19 testing

embraced internal expertise, ingenuity and cooperation

Thanks to a broad spectrum of knowledge and skills and a community-wide willingness to put in endless hours of hard work, Villanova University distinguished itself in its nimble and robust response to COVID-19 over the past year.

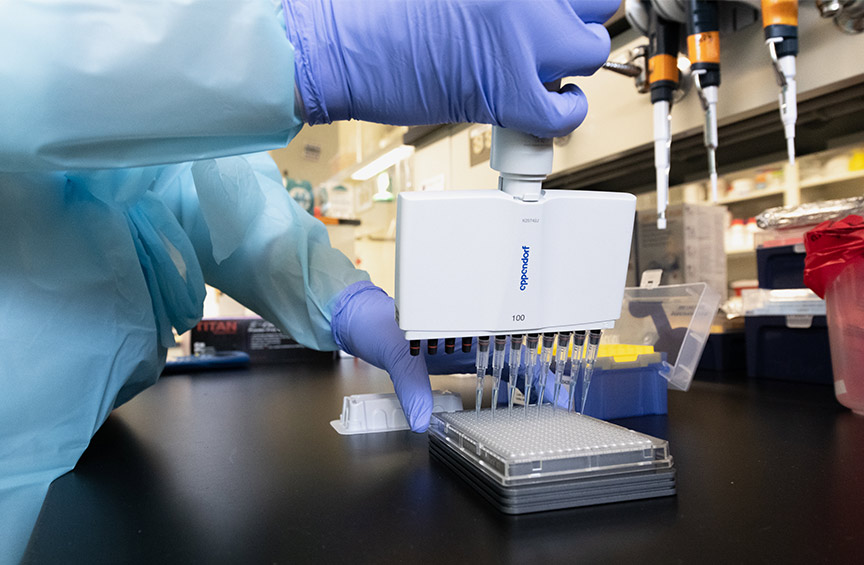

Widespread, on-campus testing was one of the key factors in that response—and it required synergy: getting the right people with the right resources and the right skills working together. Drawing from a deep well of expertise, an interdisciplinary team of faculty, staff and leaders across the University rose to the challenge.

Faced with a novel situation with many moving parts, they started with a blank slate. “With a new virus, even experts weren’t ‘expert.’ We had no easy method for diagnosis, no treatments, no vaccine. We had questions, but no answers,” says Student Health Center Director Mary McGonigle, DO, ’88 VSB. “It wasn’t if Villanova would have COVID-19, but when. We planned for uncertainty and managed change.”

A Game Plan for Testing

Early on, the University committed to a wide-ranging, inclusive search for ideas to thwart COVID-19’s impact, including contributions from many of Villanova’s own faculty experts, with the goal of operating safely throughout the academic year.

A member of Villanova’s Policy and Operations committees, Dr. McGonigle turned to Student Health Center colleagues Michael Duncan, MD, ’03 CLAS and Mary Agnes Ostick ’14 DNP, CRNP, for daily brainstorming meetings.

“We knew widespread, accurate PCR testing would be a key factor in staying open, slowing the spread and keeping infections manageable,” Dr. Duncan says.

PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing is considered the “gold standard” for diagnosing COVID-19 because it’s the most accurate and reliable test. It can detect the presence of genetic material from a virus during an infection as well as fragments of virus post-infection.

Getting PCR testing up and running on Villanova’s campus was a huge order—a testing location had to be found, equipment supplied, databases prepared, email blasts sent, follow-up responses crafted and more. “Moving parts to the University’s COVID-19 response seemed to multiply daily,” says Robert Morro, vice president for Facilities Management. “Project management was needed, so I volunteered.”

Morro’s team was instrumental in forming a game plan for the project, identifying tasks that needed completion, crafting budget expectations, procuring supplies and more. A staff in the Biology Department and Procurement Office sourced an array of equipment, chemicals, and other supplies needed to make the operation successful, working through global supply shortages.

“There was also a large IT piece that had to be considered,” says Morro. UNIT, the University Information Technologies team, proved essential. Experts on the team created a downloadable app that associated personally identifiable information with a test-tube barcode when scanned by the individual being tested.

“UNIT staff members had to parse through a massive database of students, faculty and staff to see who had already had COVID, who was on campus, who would be randomly tested on any given day,” Morro says.

When a testing station, staffed by volunteers, opened in Finneran Pavilion last fall, saliva specimens were collected in test tubes from 125 students every day. Those specimens were sent to Rutgers University for analysis, costing about $150 per test.

“We needed to ramp up to 800 tests daily, but the cost seemed prohibitive,” explains Dr. Duncan, who dared to believe complete testing could be accomplished on Villanova’s campus for about $4 per test. He approached the Biology and Engineering departments to ask who could run a PCR lab. “Thank God, Elaine Youngman raised her hand,” says Dr. Duncan.

“ There is no playbook for how to operate in a pandemic. What happened on this campus was nothing short of amazing, the definition of team spirit. ”

- Michael Duncan, MD, ’03 CLAS

Pulling Everything Together

COVID-19 is an RNA virus, and Dr. Youngman, assistant professor of Biology, is an RNA biologist. She had the expertise—what she didn’t have was a PCR machine capable of processing large test batches. University leadership was quick to approve the purchase of a $65,000 machine, which is now on track to save Villanova millions in testing costs. “With this PCR machine, our team of four can provide same-day results for up to three batches of 368 samples each,” Dr. Youngman says. “Plus, it will be a valuable teaching and research tool, post-pandemic.”

Once sustainable surveillance testing was in place, a plan for handling positive cases that arose on campus was essential. Dr. Ostick was tasked with recruiting and overseeing an army of contact tracers, all of whom completed Johns Hopkins University’s online contract tracing training.

The University provided phones, computers and intake forms, developed with UNIT specifically for the Villanova community. The customized form allowed them to gather robust information about positive patients, onset of symptoms, testing and demographics (such as their residence hall, activities and teams.) “All of that information helped us identify hotspots on campus,” Dr. Ostick says.

When students felt sick or symptomatic, they reported to the Student Health Center, with suitcases packed. Nurse practitioners and nurses, in full PPE, evaluated and tested them. “Local students (within 300 miles) who tested positive went home or were driven to dedicated isolation residences on and off campus, including The Inn at Villanova. They did not return to their residence halls,” says Dr. Ostick.

Meanwhile, contact tracers notified close contacts, who then quarantined in dedicated areas. Testing continued regularly to identify new infections. “More than 200 ‘close contact’ students removed from residence halls eventually turned positive,” says Dr. Ostick. “Can you imagine the extent of the spread if we had not done that?”

The COVID-19 effort was feet-to-the-fire in February when a post-holiday surge hit. The Student Health Center was conducting 200 tests daily. By mid-April, more than 34,000 surveillance tests had been completed in-house, with 4,000 tests a week, on average. Positive cases had dropped significantly—from an average of 40 to 70 cases per day in February to between zero and four per day in April. “My staff was in the trenches; I’m so proud of their dedication,” says Dr. McGonigle. “Everyone truly put community first.” ◼︎

NEXT IN FEATURES

A sampling of courses that inspire Villanova students to think critically and creatively