Not Your Average Marine Ecology Class

Upon arriving at Villanova in the fall semester as a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Geography and the Environment, Tory Chase, PhD, went to work to create a brand new course called Oceans in the Anthropocene. The course focused on ocean conservation, coral reefs, and marine restoration. But he also incorporated an emerging topic into his class as a focal point: science communication.

With a background in coral reef science, Chase also has a keen interest in science communication, which is the process and practice of informing, educating and distilling technical science-related topics and information to be more easily understood and learned by a general audience. According to him, science communication is a very important skill for any scientist to have.

“I ask my students to remember what it was like to go to a science museum and how interactive it was,” Chase explains. “I tell them how games, activities and demonstrations really bring people in. “

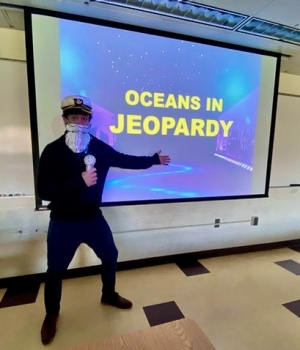

Chase heeds his own advice and during one lecture—that involved more complex terminology—he created an interactive ‘Oceans in Jeopardy’ game, which was hosted by a created character, named Captain Conservation, and incorporated components of the classic game show.

“When I was growing up, I watched Bill Nye the Science Guy or Ms. Frizzle from The Magic School Bus, and today we have David Attenborough narrating an episode of Planet Earth,” said Chase. “These characters are charismatic, show signs of leadership and can effectively tell a story. And that’s what I’m trying to show my students with a character like Captain Conservation. In the strategic steps of science communication, who communicates is important.”

Throughout the course, there are lectures completely devoted to science communication. Chase discusses topics such as goals for public scientific literacy, what science communication has looked like over the last 200 years and how it interacts with race, culture and STEM.

When the class material is more conservation and ecology-focused, Chase devotes the last few slides of class to something he calls, “Your Daily Dose of Science Communication.” The Daily Dose could discuss the power of a data table or how to tell an effective story with a photo.

“If I had two photos of coral reefs and one was healthy and one was bleached, I would want my students to understand two things,” Chase explains. “One, what are we trying to get the audience to understand in terms of message/context and two, why do we have to be extremely selective in conveying an appropriate, balanced and scientifically-sound depictions? There’s the old adage that a photo can tell a thousand words, but I think that a photo needs to tell an effective story.”

Throughout the semester, Chase’s students created a two-part science communication portfolio, taking the lecture material and turning it into practice.

For the first part of the portfolio, based on different scholarly publications, students had to create scientific memes, write a press release and act like a peer reviewer and edit a paper. The second part involved developing tweets and taking online modules that reinforced what Chase taught in class, allowing students to get a Media Skills for Scientists certificate that they can put on their resume. A ,major aspect of the second part of the science communication portfolio included creating a podcast, where students submitted 10-minute episodes. Topics focused on threats to marine life, how to conserve particular marine species, or solutions to marine issues.

Chase’s class differs from many others that feature science communication, as he doesn’t just focus on the theory or the practice – he does both. As scientists are asked to do much more in their roles, he hopes his students see the value of this course.

“What I’m trying to instill upon my students, whatever their job is going to be after Villanova, is that it’s going to involve science communication,” says Chase. “It doesn’t matter if you’re in a lab or a research student, some part of it is going to be science communication. The new generation of scientists must strive for more than just being good at science. They must also know how to successfully communicate it with society.”