Researchers Make a 110-Million-Year-Old Discovery

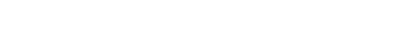

Retinosaurus hkamtiensis skeleton with scales overlying the body. CT reconstructions by Edward Stanley using synchrotron data gathered at Imaging and Medical Beamline at the Australian Synchrotron in Melbourne. Courtesy Adolf Peretti and the Peretti Museum Foundation.

Imagine being able to see the skeleton, muscles, scales, eyes or even a windpipe of an animal that was around 110 million years ago. That’s exactly what happened when Aaron Bauer, PhD, professor of Biology and the Gerald M. Lemole Endowed Chair in Integrative Biology, and a team of global researchers analyzed a piece of amber from Myanmar and discovered a lizard.

“You’re looking into the face of an animal that lived when the dinosaurs were roaming around,” Bauer said.

Compared to modern discoveries in hard rock fossil—where you just have the skeleton or an imprint—the lizard in amber looks as if it was alive yesterday. Amber, a fossilized tree resin and often valued for its use in jewelry and other decorative purposes, has yielded discoveries of other small vertebrates. In fact, the oldest known example of mosquitoes comes from Burmese amber. The team is also doing new research to see if the lizard could be as old as 120 million years.

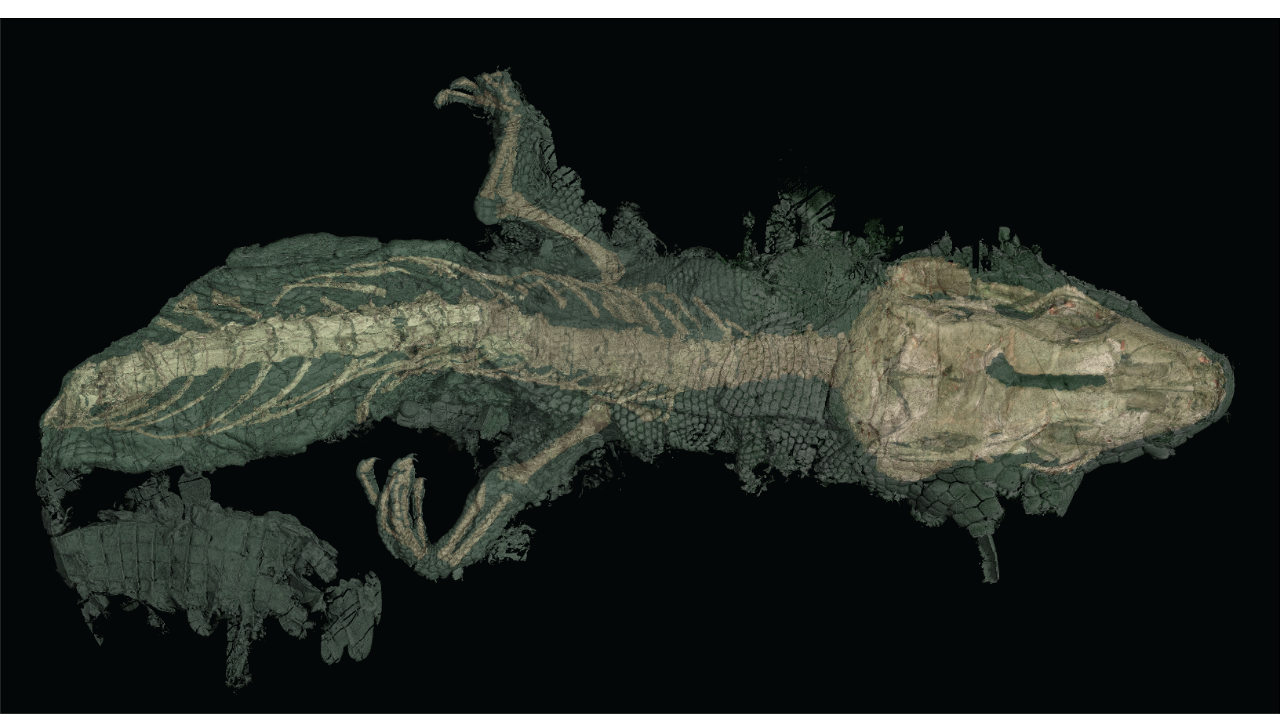

A) Fossil embed in amber, B)3D model of the body dorsal scales, C) Detail of the ventral scales of the head, D and E) Lateral views of the head. CT reconstructions by Edward Stanley using synchrotron data gathered at Imaging and Medical Beamline at the Australian Synchrotron in Melbourne. Courtesy Adolf Peretti and the Peretti Museum Foundation.

Amber is formed from tree resin, which protects trees from gaps in bark. The resin hardens, trapping small insects, spiders and vertebrates, and over time turns into amber. Anything caught in the amber would have to be small or weak enough to not escape, so the lizard discovered was rather small. About 35 millimeters, to be exact.

It may sound like this was an easy discovery, but to find a single lizard, one needs to search through tens—if not hundreds—of thousands of amber pieces. The amber came from a mine in Myanmar and was analyzed through a CT scan, which allowed the team to create 3D renderings of the lizard.

This new finding provided the team a glimpse into what was happening into the evolution of lizards before they were set on their modern path. The discovery, Retinosaurus hkamtiensis, is the first definite representative of a group of lizards known as scincoideans, a group that today includes skinks, armored lizards and night lizards. Living night lizards are found much closer to home in the southwest US, Central America and Cuba. So perhaps the night lizards, thought to have evolved in f the new world, came into existence literally across the world and are much, much older than scientists had imagined.

The findings were published recently in the journal, Scientific Reports.