Sister Cora Marie Billings ’67 CLAS entered the Religious Sisters of Mercy Motherhouse in Merion, Pa., on Aug. 22, 1956.

PHOTO: SISTER CORA MARIE BILLINGS, RSM

Villanova History professor uncovers the rich history and untold stories of black nuns in the American Catholic Church

BY QUEEN MUSE

Sister Cora Marie Billings ’67 CLAS entered the Religious Sisters of Mercy Motherhouse in Merion, Pa., on Aug. 22, 1956.

PHOTO: SISTER CORA MARIE BILLINGS, RSM

As a graduate student at Rutgers University, Shannen Dee Williams came across an image of four black nuns in a 1968 Pittsburgh Courier article announcing the formation of the National Black Sisters’ Conference in Pittsburgh. She was in search of a topic for a short seminar paper. What she found was a story that sparked an excitement and curiosity that would drive the focus of her research for years to come.

“After that moment, I knew I wanted to know as much as possible about this organization and the women who founded it,” says Dr. Williams, who now holds the Albert R. Lepage Endowed Assistant Professorship in History at Villanova.

That was 2007. Before then, the only black nun Dr. Williams had ever seen was Whoopi Goldberg’s Sister Mary Clarence in the Sister Act movie franchise. “I had so many questions,” she says. “Of course I wondered, ‘How was it possible that I, a cradle Catholic, the daughter of the first black woman to graduate from the University of Notre Dame, had no idea that black nuns existed?’”

Despite the invisibility of black sisters in the annals of Catholic history, Dr. Williams discovered a rich tradition of black women participating in religious leadership as early as the first century.

“The story of the real ‘Sister Act’ (in the United States) is how generations of African American women and girls fought against racial segregation and exclusion to answer God's call in their lives and minister as women religious, as sisters,” she says.

Dr. Shannen Dee Williams presented Sister Cora Marie for an honorary doctoral degree at Commencement in May.

PHOTO: JOHN SHETRON

At Commencement this past May, Dr. Williams proudly introduced one of these trailblazing African American women religious to receive an honorary doctoral degree from Villanova.

“Father President, for her leadership in breaking down racial barriers in our Church and in honor of all of the lives that she has touched and inspired over the years as a pioneering sister, teacher, campus minister, pastoral coordinator and all-around freedom fighter, it is with tremendous joy and the greatest honor that I present to you for the degree of Doctor of Humane Letters, Honoris Causa, Sister Cora Marie Billings ’67 CLAS.”

It was a full-circle moment for Dr. Williams—Sister Cora Marie was one of the sisters who established the National Black Sisters’ Conference in 1968 and inspired her research for the past 12 years. Sister Cora Marie was one of several Sisters of Mercy at that conference.

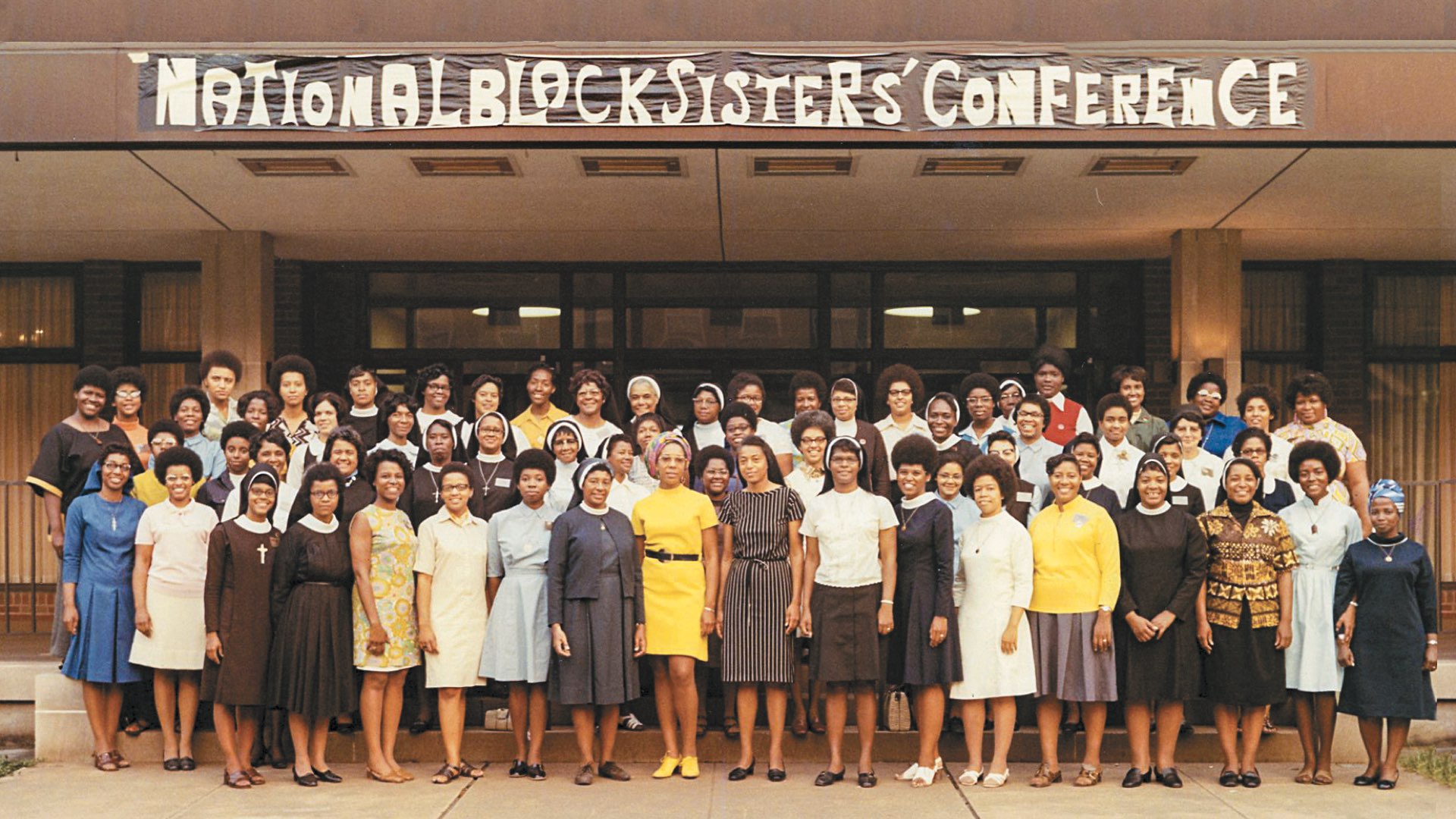

Early members of the National Black Sisters’ Conference outside the conference headquarters in Pittsburgh in the early 1970s. Sister Cora Marie is fourth from the left in the front row.

PHOTO: SISTERS OF CHARITY OF NAZARETH

In 1956, Sister Cora Marie had desegregated the Mercy Community in Merion, Pa., and begun blazing a path of being the “first” or the “only” in many settings over her six-decade career as a Catholic nun. She is one of many pioneering African American women religious Villanova counts among its alumnae.

Early in the 20th century, new state laws began requiring parochial school educators to obtain formal certifications and college degrees to teach. This presented an additional challenge for the nation’s black teaching sisterhoods, which had been established in response to the exclusionary admissions policies of other religious orders. Most Catholic institutions of higher education at the time did not admit African Americans, whether they were Catholic or not.

Villanova was one of the first Catholic institutions of higher education to open its doors to black women religious, most notably the Oblate Sisters of Providence, headquartered in Baltimore, Md., after World War I.

Sister Cora Marie hails from a family of devout African American Catholics who fought against racist barriers to participate in the Catholic faith and wider American life. Her pioneering great-grandparents had labored as slaves under Catholic auspices in Washington, D.C. Amid much opposition, Billings’ grandfather, John Aloysius Lee Sr. became the first African American person allowed to play in Philadelphia’s Catholic high school basketball league in 1902. The city later built the John A. Lee Recreation Center to honor his legacy of fighting for black inclusion in local athletics. His daughters, Susan Grace Lee and Bertha Amelia Theresa Lee, however, were denied admission into religious life in Philadelphia in the 1940s because of the color of their skin.

Left: Sister Cora Marie in May 1957 with her father, Jesse Billings, and her grandfather, John A. Lee Sr., in Merion, Pa. Right: Sister Cora Marie with her grandmother Gertrude A. Lee and her aunt Sister Mary Paul Lee, OSP, in June 1964 in the garden of St. Ignatius Convent.

PHOTOS: SISTER CORA MARIE BILLINGS, RSM

It’s a dichotomy Sister Cora Marie still faces: knowing the undeniable barriers faced by her aunts, who ultimately became Oblate Sisters of Providence, and being the one who ultimately knocked those same barriers down. “I realize that, to get to where I am, I’m standing on the shoulders of ancestors,” she says.

Kicking off Villanova’s 2019 Black History Month celebration earlier this year, Sister Cora Marie shared these thoughts and experiences during a fireside chat with Dr. Williams in the St. Thomas of Villanova Chapel.

Ultimately, Sister Cora Marie says the experiences of her ancestors fueled her determination to become a part of the Church and work to ensure the same opportunity for other black sisters in the faith. “I have never seen a system changed by somebody from the outside,” she says. “I knew in order to change the Church, I had to remain within the system and look for the strategies and people who were willing to help me change it.”

Over the past 63 years, she’s done just that. In the 1960s, she became the first African American person to teach at an all-white grade school in Levittown, Pa., and the first African American sister to teach in a Catholic high school in Philadelphia. She went on to become the first African American sister to work as a campus minister at Virginia State University, and then became the first African American nun to lead a US Catholic parish, serving as the pastoral coordinator for St. Elizabeth Parish in North Richmond, Va., for 14 years. She also led the Diocese of Richmond’s Office for Black Catholics for 25 years and was director of the Human Rights Council for the state of Virginia from 2007 to 2010.

“Her story and the story of her family’s extraordinary journey from slavery to freedom in the Catholic Church typify what many scholars call the uncommon faithfulness of the black Catholic community,” Dr. Williams says. “It mirrors that of so many sisters who understood that segregation and racism have no place in the universal Church and fought to make the Church live up to its Catholic ideals.”

“I knew in order to change the Church, I had to remain within the system and look for the strategies and the people who were going to help me change it.”

Sister Cora Marie Billings, RSM, ’67 CLAS

A preeminent scholar, Dr. Williams has traveled across the country speaking about the history of black Catholic sisters to religious communities and assemblies, including the Leadership Conference of Women Religious assembly in Atlanta (pictured here).

PHOTO: MICHAEL ALEXANDER/GEORGIA BULLETIN

Dr. Williams has spent the past 12 years conducting extensive research on the lives and labors of these sisters, including more than 100 interviews with former and current black and white nuns. She’s poured all of these newly uncovered truths about the roles of black sisters in American Catholic history into the manuscript for her first book, Subversive Habits: The Untold Story of Black Catholic Nuns in the United States.

Dr. Williams’ research suggests black sisters were not omitted from American Catholic history by accident. Many black women and girls who had been educated by white nuns were later denied admission into the religious communities of their educators on the basis of race alone. Rare exceptions were made for black women and girls with light skin prior to World War II. Still, others who did desegregate, or even help to establish, white congregations were often later excluded from the histories of those communities.

“I keep the images and prayer cards

of black sisters close because their tradition of great and steady faithfulness inspires me.”

Dr. Shannen Dee Williams

Dr. Williams' work is especially timely now, not only because of its historical originality but also because of the changing demographics in the Catholic Church, which is projected to experience its greatest growth in Africa, Asia and Latin America over the next three decades. “It’s particularly important that we understand who makes up the Church and recognize the contributions of those who made the Church what it is today,” she says.

Her book will provide the first full historical examination of black Catholic sisters in the United States, and it will be a transformative work for anyone who reads it, according to Maghan Keita, PhD, director of the Africana Studies Program and professor of History at Villanova.

“It’s going to be an eye-opener. It’s definitely going to prompt a lot of conversation,” he says. “Dr. Williams’ efforts to highlight the contemporary notions of people of African descent, and particularly African American women in the Catholic Church, invites us to go back and take a closer look at the history of the Catholic Church in ways that we never have before.” ◼︎

This summer, specialists installed a new stained glass window in Villanova's Corr Chapel depicting Servant of God Sister Thea Bowman. The Rev. Richard Cannuli, OSA, MFA, ’73 CLAS, professor of Studio Art, designed the window highlighting the Franciscan nun, who is one of six black Catholics who are being considered for canonization.

Sister Thea changed the fabric of the American Catholic Church in the late 20th century, but her story is not well-known, says Shannen Dee Williams, PhD, assistant professor of History. The granddaughter of slaves and the only African American member of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration in the Diocese of La Crosse in Wisconsin, Sister Thea was known for her powerful preaching and singing at Church gatherings across the country.

Though the four-stage process for sainthood can take decades or even centuries, Dr. Williams believes the causes of Sister Thea and other black Catholics further encourage the Church to embrace African Americans as part of the American Catholic experience.

“Even if they never become saints, the fact that their causes have been formally opened means we’ll have an opportunity to tell their stories in a host of new ways,” Dr. Williams says.

The window depicting Servant of God Sister Thea Bowman in Corr Chapel, which also features Servant of God the Rev. Bill Atkinson, OSA, ’73 CLAS in its other panel, was donated by the Russomano family — Michael ’79 VSB and Deborah Russomano; James ’82 VSB and Anne Russomano; Frank ’87 VSB and Aimee Russomano; and Donna Maria ’88 CLAS and Gregory DeRosa — in memory of their parents, Michael and Frances Russomano.

PHOTO: VILLANOVA UNIVERSITY